Early Brethren Life in America

Written by Ronald J. Gordon ~ Published February, 1996 ~ Last Updated: October, 2024 ©

This document may be reproduced for non-profit or educational purposes only, with the

provisions that the entire document remain intact and full acknowledgement be given to the author.

fter enjoying a temporary respite in the district of Wittgenstein from religious persecution, the early Brethren migrated across the European landscape to escape renewed harassment and intolerance. Alexander Mack led one group from Schwarzenau where they had organized in 1708, to the small village of Surhuisterveen in northeastern Holland around 1720. John Naas and Peter Becker moved another group of peace desiring Brethren from the expansion project in Marienborn to the city of Krefeld in 1715. This haven for Mennonites was an industrial textile city along the Rhine River under the temporary jurisdiction of the King of Prussia. In 1729, Mack transported his Anabaptist / Pietist refugees to Pennsylvania where the guarantee of religious expression seemed certain at last. William Penn was promising economic freedom and cheap land in order to build his dream of a Christian state. Embarking from Rotterdam on the ship Allen, his party would arrive in Philadelphia harbor on September 11, 1729. Preceding him by ten years, however, was the Peter Becker group from Krefeld who arrived with about twenty families in 1719. Both new arrivals settled in a northwest suburb of Philadelphia called Germantown, most probably because of it’s kindred ethnic culture. This area was previously established in the 1680’s by Mennonites who also came from Krefeld. The congregation at Germantown would serve as a missionary base for the Brethren who spread their gospel of radical transformation to surrounding territories. Here are some of the more significant events in the early migration and expansion of the Brethren in America.

fter enjoying a temporary respite in the district of Wittgenstein from religious persecution, the early Brethren migrated across the European landscape to escape renewed harassment and intolerance. Alexander Mack led one group from Schwarzenau where they had organized in 1708, to the small village of Surhuisterveen in northeastern Holland around 1720. John Naas and Peter Becker moved another group of peace desiring Brethren from the expansion project in Marienborn to the city of Krefeld in 1715. This haven for Mennonites was an industrial textile city along the Rhine River under the temporary jurisdiction of the King of Prussia. In 1729, Mack transported his Anabaptist / Pietist refugees to Pennsylvania where the guarantee of religious expression seemed certain at last. William Penn was promising economic freedom and cheap land in order to build his dream of a Christian state. Embarking from Rotterdam on the ship Allen, his party would arrive in Philadelphia harbor on September 11, 1729. Preceding him by ten years, however, was the Peter Becker group from Krefeld who arrived with about twenty families in 1719. Both new arrivals settled in a northwest suburb of Philadelphia called Germantown, most probably because of it’s kindred ethnic culture. This area was previously established in the 1680’s by Mennonites who also came from Krefeld. The congregation at Germantown would serve as a missionary base for the Brethren who spread their gospel of radical transformation to surrounding territories. Here are some of the more significant events in the early migration and expansion of the Brethren in America.

|

|

|

reams become reality with enough persistence and hard work. William Penn had a dream of establishing a Christian state in the New World, but populating his 1681 land acquisition from King Charles II of England, necessitated his finding prospective citizens who would ensure that it remained Christian. For many years, he traveled around Europe recruiting Mennonites, Pietists, and other religiously persecuted groups including Quakers (Society of Friends) from his native England. The latter gained control of the early legislature and strictly ruled the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania along spiritual principles, which received frequent protests from secularists who resented the imposition of spiritually derived laws. Governors faithful to the Proprietary Party (the William Penn family and related interests) protested the Quakers refusal to maintain a peace keeping militia because numerous Indian tribes were raiding settlements without fear of reprisal. Into this political arena came the - peace desiring - freedom loving - weary of running from authorities - Schwarzenau Brethren. Christopher Sauer immediately sided with the more kindred Quakers and unabashedly influenced their election to the legislature through the power of his press (see below).

reams become reality with enough persistence and hard work. William Penn had a dream of establishing a Christian state in the New World, but populating his 1681 land acquisition from King Charles II of England, necessitated his finding prospective citizens who would ensure that it remained Christian. For many years, he traveled around Europe recruiting Mennonites, Pietists, and other religiously persecuted groups including Quakers (Society of Friends) from his native England. The latter gained control of the early legislature and strictly ruled the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania along spiritual principles, which received frequent protests from secularists who resented the imposition of spiritually derived laws. Governors faithful to the Proprietary Party (the William Penn family and related interests) protested the Quakers refusal to maintain a peace keeping militia because numerous Indian tribes were raiding settlements without fear of reprisal. Into this political arena came the - peace desiring - freedom loving - weary of running from authorities - Schwarzenau Brethren. Christopher Sauer immediately sided with the more kindred Quakers and unabashedly influenced their election to the legislature through the power of his press (see below).

William Penn was born October 14, 1644 to Admiral Sir William Penn and Margaret Jasper. His youthful life involved managing some of his fathers huge estates in Ireland. Following his conversion to Quakerism he became involved in the Quaker cause, a pursuit which landing him in jail many times for his radical advocacy for personal, property, and religious rights. Penn married Gulielma Maria Springett in 1672, and later traveled to America in the company of George Fox, the founder of Quakerism. Fox was led to believe that an inner voice which he called the 'Inner Light' was a true witness of Christ to all believers through the Holy Spirit. In 1647, he began preaching about this inner witness to a politically troubled England. As is true of so many religious movements, the appellation Quaker was a term of derision. It originated as an insult from a British judge when Fox told him that he should 'tremble at the Word of the Lord' to which the judge then called him a Quaker.

Penn called in a debt that was owed to his father by Charles II and the King of England took this opportunity to settle the matter by giving the son New World property in lieu of cash, something of which the monarch possessed in short supply. Penn had a utopian dream for this tract of land where he could establish a godly society, a "holy experiment" as he explained it to Pennsylvania land agent James Harrison. A society that would espouse virtue and serve as an example to the rest of the world. The charter became official on March 4, 1681 and deeded about 45,000 acres to Penn with almost unlimited power to rule. In August of 1682, he gained the rights to Delaware from James the Duke of York, and set about establishing a Christian State in this newly acquired territory that would additionally serve as a haven for all religiously oppressed groups, especially the industrious German Pietists and Mennonites. Penn made numerous trips into Europe in order to generate enthusiasm for his Christian experiment and Fox accompanied him frequently. Both were successful in convincing many war weary people to emigrate to America. It is unknown if Penn or Fox had direct contact with any Brethren groups but perhaps the latter gained knowledge of the offer and were influenced by the prospect of religious freedom and cheap land, because most areas where Brethren found refuge in Europe were also some of the most impoverished.

arrowing were the experiences of people who risked their lives and property to cross the Atlantic Ocean from Europe to America during the Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries. The season for passage began in early May and ended in late October with each westerly voyage from England requiring at least seven to eight weeks with good tail winds, and often ten to twelve weeks if the winds were not favorable. A typical journey for refugees fleeing religious persecution in Europe or indentured servants contracting years of labor for the cost of passage would often begin in Rotterdam or Amsterdam and then proceed to England for supplies. Accommodations were sparse. Personal living space was limited to just barely enough room for a person to lay down to sleeping. Most ships would dock in England for several days while cargo and provisions were loaded. Passengers would spend money or eat some of what little food they had brought for the journey, only to later discover on the open sea that those few morsels would have eased the hunger that will haunt them for most of the voyage. Far too many people did not realize, nor were they prepared for the actual degree of human misery that lay before them. Sailing vessels of this period were grossly unsanitary because of the accumulation of repeated vomits, dysentery, sweat, mildew, and rot. The lower decks were usually filled with stench.

arrowing were the experiences of people who risked their lives and property to cross the Atlantic Ocean from Europe to America during the Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries. The season for passage began in early May and ended in late October with each westerly voyage from England requiring at least seven to eight weeks with good tail winds, and often ten to twelve weeks if the winds were not favorable. A typical journey for refugees fleeing religious persecution in Europe or indentured servants contracting years of labor for the cost of passage would often begin in Rotterdam or Amsterdam and then proceed to England for supplies. Accommodations were sparse. Personal living space was limited to just barely enough room for a person to lay down to sleeping. Most ships would dock in England for several days while cargo and provisions were loaded. Passengers would spend money or eat some of what little food they had brought for the journey, only to later discover on the open sea that those few morsels would have eased the hunger that will haunt them for most of the voyage. Far too many people did not realize, nor were they prepared for the actual degree of human misery that lay before them. Sailing vessels of this period were grossly unsanitary because of the accumulation of repeated vomits, dysentery, sweat, mildew, and rot. The lower decks were usually filled with stench.

People suffered from ill preserved food stores, constipation, headaches, infestations of lice, a multitude of maladies resulting from impure water, and of course the ubiquitous affliction of seasickness. Add to this the emotional fatigue of unrelenting weather conditions such as cold, dampness, heat, and storms that would rage for days. Passengers were repeatedly thrown against each other in step with the rhythmic pounding of each wave. Homesickness began to plague many because they remembered all too well the comfort of even the most humble dwelling. So bad did the conditions become after many weeks, that people longed to be home, if even to sleep in a barnyard. Psychological factors then begin to play through manifestations of impatience and unceasing frustration. Curses and threats of harm were frequently exchanged, and occasionally tensions escalated into brawls, even between members of the same family. They cursed and berated each other. Stole from one another. Constant anxiety for life and safety began to turn into hopelessness,

Death was a steadfast companion of both passengers and crew for many would perish. Burial at sea can be an especially difficult and trying experience. One does not have the expected proper time for remorse because the body must be cast overboard in a short period of time. The sea does not allow family members to return to an exact spot in order to grieve as is true of a land based cemetery where people can repeatedly return, where flowers can serve as a visible closure, and the certainty that graves usually remain unmolested. Death at sea can be a cruel experience. You cannot return. There is the haunting reality that the body will probably be eaten. Family members reproach each other for persuading them to make the journey. Wives reproached their husbands for children that were lost. Husbands lamented most piteously for convincing their family to make the journey. Children bemoaned parents for their helplessness. Witness accounts record unbelievable despair and misery. As more and more people die, it becomes almost impossible to console the relatives.

"Many hundred people necessarily die and perish in such misery, and must be cast into the sea, which drives their relatives or those that persuaded them to undertake the journey, to such despair that it is almost impossible to pacify or console them. In a word the sighing and crying and lamenting on board the ship continues day and night, so as to cause the hearts of even the most hardened to bleed when they hear it."

On the Misfortune of Indentured Servants, Gottlieb Mittelberger, 1754.

he immigrating Brethren, also known as Dunkards because they “dunk’ed ” converts three times forward (thus Trine Immersion, see also Brethren Groups) had too frequently lost their religious liberty while in Europe and were now hoping that their horrific Atlantic crossings had not been in vain. Brethren had settled in some of the most impoverished areas of a war ravaged Europe and the promise of cheap land in Pennsylvania and the freedom to worship as one chose seemed irresistible. Now they spent the next several years establishing and realizing their dream. In reverent quietude following a four year silence of religious activity, Brethren gathered along the northern bank of a gentle stream to inaugurate their American presence through the rite of baptism. The ice was broken on Christmas Day in 1723 when resident and newly arriving Brethren decided to form the Germantown Congregation, baptizing six persons through trine immersion in the nearby Wissahickon Creek (modern Fairmount Park). Martin Urner was first, along with his wife Catherine, Henry Landis and wife Elizabeth Naas-Landis, Frederick Lang, and John Mayle. Urner later became the first pastor of the Coventry congregation when it formed in November of the following year. October of 1724 witnessed several Brethren trek from the newly formed Germantown congregation on their first missionary journey to other Brethren settlements at Indian Creek, Falckner’s Swamp, Oley, and Coventry where they preached the heart of the Brethren message of radical conversion.

he immigrating Brethren, also known as Dunkards because they “dunk’ed ” converts three times forward (thus Trine Immersion, see also Brethren Groups) had too frequently lost their religious liberty while in Europe and were now hoping that their horrific Atlantic crossings had not been in vain. Brethren had settled in some of the most impoverished areas of a war ravaged Europe and the promise of cheap land in Pennsylvania and the freedom to worship as one chose seemed irresistible. Now they spent the next several years establishing and realizing their dream. In reverent quietude following a four year silence of religious activity, Brethren gathered along the northern bank of a gentle stream to inaugurate their American presence through the rite of baptism. The ice was broken on Christmas Day in 1723 when resident and newly arriving Brethren decided to form the Germantown Congregation, baptizing six persons through trine immersion in the nearby Wissahickon Creek (modern Fairmount Park). Martin Urner was first, along with his wife Catherine, Henry Landis and wife Elizabeth Naas-Landis, Frederick Lang, and John Mayle. Urner later became the first pastor of the Coventry congregation when it formed in November of the following year. October of 1724 witnessed several Brethren trek from the newly formed Germantown congregation on their first missionary journey to other Brethren settlements at Indian Creek, Falckner’s Swamp, Oley, and Coventry where they preached the heart of the Brethren message of radical conversion.

Then turning west into the Conestoga territory (Lancaster) in November, they baptized many persons including fellow German separatist Conrad Beissel. This mystical visionary would later break with the Conestoga Brethren and establish his own faith experiment at Ephrata Cloister. Beissel willfully but disdainfully submitted to Peter Becker, the undisputed leader of the German Baptist Brethren prior to the later arrival of their founder Alexander Mack in 1729. Brethren historians are occasionally asked: "Why did the early Brethren wait four long years to establish a congregation in America?" "Why didn't a fellowship loving people start a congregation right away?" There may be several reasons and history is usually a mixture of different elements playing together such as, harsh frontier conditions, difficulty in creating homesteads, wretched eight to ten week Atlantic crossing, and perhaps lingering emotions of bitterness from the Hacker affair at Krefeld (see European Origin: Marienborn to Krefeld).

One undocumented account suggested that lingering emotions over the Hacker situation erupted again between members of the Becker party during their 1719 crossing. This might easily account for the immediate silence and distance that existed between the early Brethren settlements. A few families remained in Germantown, but several moved far beyond its Mennonite sub-cultural boundary, north along the Schuylkill River or west into the Conestoga territory. The probability of dispersed families coming together over great distances for any particular reason would certainly depend on the unique importance of the event. So why then did the Brethren journey to Germantown in December of 1723 from their many settlements? It was rumored, although incorrectly, that Krefeld associate pastor Christian Libe had just arrived in America and would naturally begin preaching. It is a credit to the Brethren’s willingness to forgive, because this is the very man who caused most of the bitterness in Krefeld. It was Libe who had placed Hacker under the ban (similar to, but not quite the same as excommunication) for marrying outside the faith. Christian Libe was described as a gifted and powerful speaker, passionate and temperamental, a strident evangelist who had been imprisoned (1714) for two years in the galleys for preaching in Switzerland. When the Brethren arrived at Germantown with the hope of listening to his fiery sermons, only to realize that the news was false, they diverted their disappointment toward a positive conclusion by organizing the first Brethren congregation in America. Germantown became known as the Mother Church. Distant settlements looked to this congregation for guidance and wisdom. It was here that publishers Christopher Sauer and Son printed the first German Bible in the American colonies (See below). His German newspaper the Pennsylvania Report circulated and rivaled other publishers including Benjamin Franklin. At one brief period, news was printed and read in German before the English version was available from any other source. German emigrants throughout colonial America looked to Germantown as the source of their news and literature. Meeting in homes before the much later use of a special meeting house, Sauer opened his own home to the newly founded flock. Although the Brethren were experiencing rapid growth in other more rural areas, Germantown remained the Mother Church. Even if only symbolic, distant Brethren eyes gratefully looked toward this first congregation, deeming it as both a heartbeat and a touchstone.

aving been the first congregation to be established by the Brethren in the New World, this appellation also derived from other considerations: many founding personalities were buried there and Germantown continued to be the principal focus of German speaking non-Brethren until well into the next century. Peter Becker organized the first group of emigrating Brethren. He was born in Dudesheim, Germany, and became acquainted with the Brethren in the Marienborn district. Becoming deeply involved in their activities, he followed them to Krefeld were John Naas was the presiding Elder. After the Krefeld congregation experienced a rift in harmony over the marriage of a Brethren minister to a non-Brethren woman, one group decided to leave for Pennsylvania under the leadership of Peter Becker.

aving been the first congregation to be established by the Brethren in the New World, this appellation also derived from other considerations: many founding personalities were buried there and Germantown continued to be the principal focus of German speaking non-Brethren until well into the next century. Peter Becker organized the first group of emigrating Brethren. He was born in Dudesheim, Germany, and became acquainted with the Brethren in the Marienborn district. Becoming deeply involved in their activities, he followed them to Krefeld were John Naas was the presiding Elder. After the Krefeld congregation experienced a rift in harmony over the marriage of a Brethren minister to a non-Brethren woman, one group decided to leave for Pennsylvania under the leadership of Peter Becker.

Arriving in 1719 they quickly established farms and small businesses. They were finally enjoying religious freedom and rest from constant persecution under the three main government aligned churches of Europe (Catholic, Lutheran, and Reformed). German districts required their citizens to adopt the faith of that district and the Big Three repeatedly proclaimed to all dissidents: "Convert, leave, or die." As the expansion of the Brethren continued, there were three congregations in America by the winter of 1724: Germantown, Coventry, and Conestoga. The arrival in 1729 of the Alexander Mack party at Germantown appeared to solidify the Brethren in America, if for no other reason than the fact that their founder was now in their midst. When the notable personage of John Naas arrived in 1733, the immigration of the Brethren seemed to be complete since there is no record of a Brethren congregation anywhere in Europe beyond this period.

Returning to Germantown following the departure of his wife Maria to the Ephrata Cloister, Christopher Sauer I built a large 60x60, two story house to serve as both a residence and place of business. The second floor of this building was used by the Germantown Congregation for worship until his death in 1758. Movable hinged partitions could be opened to provide a large room for worship services and later closed for family purposes. A typical Sunday experience would be the gathering of the congregation to a member’s home for worship and instruction in the morning followed by a noon meal. Adults generally spent the afternoon in fellowship, private conversations, prayer, and singing while children played. These gatherings were so edifying and harmonious that it was a contributing factor to the accumulation of new members. This style of worship combined with rewarding fellowship stood in stark contrast to the high liturgical services of Europe. It was novel and attractive. Germantown’s urban congregation differed greatly from its scattered rural sisters in that it was comprised mostly of artisans, craftsmen or small business owners. Rural churches were mostly comprised of farmers or people involved with some form of agriculture. Following the death of Sauer I in 1758, the Germantown Brethren gradually perceived the need for a separate meeting house. Their congregation was large and the young Sauer II business and family were both becoming large enough to demand the space of that second floor meeting room.

In 1760, a small tract of land belonging to a Peter Shilbert was donated to the Germantown congregation and the deed was secured by it’s four trustees, Sauer II, Mack II, George Schreiber, and Peter Leibert. An original log cabin had been replaced in 1756 with a small stone dwelling of a Johannes Pettikoffer and his wife Ann Elizabeth. This couple sold the house in 1739 when they moved to the Ephrata Cloister. Shilbert also donated additional land for a burial ground. After remodeling the Pettikoffer house and removing interior walls, members still considered it too small for worship. Before long, a square, stone meeting house was erected immediately to the rear of the Pettikoffer house in 1770 with an outside stairway to a Loft where items for Love Feast & Communion were stored. Guests at communion also lodged in this upper room because of the great distances they needed to travel. Although the Loft has been removed from the front part of the original structure (now a museum), a small two foot wide upper section has been preserved along the front wall for historical interpretation, including furniture and communion elements of the period. About 1880 the meeting house was again remodeled with the outside stairway to the Loft was removed and the exterior walls plastered. Still needing additional space, a much larger extension was constructed immediately behind the square stone meeting house in 1896 with yet a subsequent addition extending to the right of this rear addition in 1915. The joint of this extension is still visible on the present roof (see above color photo). With the construction of the square, stone meeting house in 1770 the Pettikoffer house was used for widows and old folks until 1861. During an outbreak of Yellow Fever which struck Philadelphia in 1793, the Brethren opened their nearly vacant burial ground to outsiders. In later years, Brethren saints from other grave locations were also reburied in the new cemetery. When the government arrested Christopher Sauer II and seized his business and property during the Revolutionary War, the Germantown Meeting House narrowly escaped confiscation because Sauer was listed as a trustee. Soldiers briefly occupied the grounds, and only with urgent pleadings from other trustees was it spared by the authorities. Germantown remained the focus of activity for all Brethren settlements. Her joys and trials frequently became their own, principally because as emigrants they entered America through Her doors of hospitality. Germantown was a Mother Church that symbolically gave birth to many daughter churches by sending preachers and evangelists great

erman printing was introduced to the American colonies and dominated by the Wittgenstein immigrants Christopher Sauer I (pronounced "sour") and his son Christopher II which included the first German Bible and the first German newspaper. Additionally, the printing press of this father and son team was also a powerful lobbying device to maintain Quaker preeminence in the Pennsylvania legislature, opposed by the Proprietary Party that was largely composed of the growing William Penn family, most governors, and related interests. The Penns were chiefly concerned that their land would not be taxed and were strong proponents of a militia to quell Indian uprisings -- the Sauers fell on opposite sides of both issues. Another foe of the Sauers was Benjamin Franklin who also operated a printing business in nearby Philadelphia and endeavored to corner their influence by monopolizing his notable control over paper and ink in this area of the colonies, and disdainfully referred to Germans as "Dutch." This competitiveness eventually led to the Sauers manufacturing their own printing supplies and distribution system. German culture was generally knitted under one voice by the Sauers who encouraged voting for candidates that would support typically Brethren issues. The fledgling Germantown congregation met for worship in the home of this prosperous businessman, where the second floor of the Sauer I residence had movable partitions so that family members could enjoy individualized compartments, yet when opened, a larger room could then accommodate the congregation for worship services. From 1731 until the death of Christopher I in 1758, this home was the principal meeting place of the Germantown Congregation.

erman printing was introduced to the American colonies and dominated by the Wittgenstein immigrants Christopher Sauer I (pronounced "sour") and his son Christopher II which included the first German Bible and the first German newspaper. Additionally, the printing press of this father and son team was also a powerful lobbying device to maintain Quaker preeminence in the Pennsylvania legislature, opposed by the Proprietary Party that was largely composed of the growing William Penn family, most governors, and related interests. The Penns were chiefly concerned that their land would not be taxed and were strong proponents of a militia to quell Indian uprisings -- the Sauers fell on opposite sides of both issues. Another foe of the Sauers was Benjamin Franklin who also operated a printing business in nearby Philadelphia and endeavored to corner their influence by monopolizing his notable control over paper and ink in this area of the colonies, and disdainfully referred to Germans as "Dutch." This competitiveness eventually led to the Sauers manufacturing their own printing supplies and distribution system. German culture was generally knitted under one voice by the Sauers who encouraged voting for candidates that would support typically Brethren issues. The fledgling Germantown congregation met for worship in the home of this prosperous businessman, where the second floor of the Sauer I residence had movable partitions so that family members could enjoy individualized compartments, yet when opened, a larger room could then accommodate the congregation for worship services. From 1731 until the death of Christopher I in 1758, this home was the principal meeting place of the Germantown Congregation.

BIRTHPLACE IN WITTGENSTEIN

There is difference of opinion on the birthplace of Johann Christoph Sauer Sr. - taylor, farmer, and printer. Martin G. Brumbaugh states in A History of the German Baptist Brethren (p. 341) that Sauer I was born in 1693 at Laasphe near Berleberg, Germany, while Stephen Longenecker avers in The Christopher Sauers (p. 11) that he was born only days before his infant baptism on February 2, 1695 in Ladenburg on the Neckar River. Since there is a recording of this baptism in the Reformed Church book at Ladenburg and no written record at Laasphe, credibility appears to lean towards the Longenecker account. After the death of his father in 1701, his widowed mother took her children to Wittgenstein and settled in the village of Laasphe. As a youth, he befriended many Anabaptists including Alexander Mack and the Brethren. His marriage to Maria Christina produced only one child, a son Christopher II while at Laasphe on September 26, 1721. Bound for America, Sauer and wife and three year old son left from Rotterdam on August 3, 1724 and arrived at Germantown in October. After about two years they moved to the Conestoga (Lancaster) territory along Mill Creek where they began farming, since tailoring did not prove very successful in the Philadelphia area. It was here that Sauer met Conrad Beissel, the leader of the fledgling Conestoga Brethren. Gradually, it became noticeable that Beissel was more intent on persuading the congregation to accept his own varied and mystical interpretations of spiritual living. In December of 1728, he openly declared his independence from the Brethren as he instructed follower Jan Meyle to rebaptize him in the Conestoga Creek. He soon moved to Ephrata and later established a formal colony in 1732 to pursue his own vision of spiritual mysticism. The repeated attempts of the Germantown Brethren to reconcile Beissel to the fold where in vain. His vibrant personality and eloquent speaking abilities endeared other Brethren and attracted many outside converts. There was a gradual exodus from many Brethren settlements to the Cloister at Ephrata, especially following the death of Alexander Mack in 1735 (founder of the Schwarzenau Brethren). In the wake of Mack’s influence, Beissel achieved prominence and embarked on a steady course of proselytizing which was immensely successful. He literally moved the entire Brethren congregation at Falckner’s Swamp to Ephrata. As many Brethren were enticed to leave their congregations and join the cloistered dwellers, Maria Sauer also left husband and son in 1730 to enlist in Beissel’s mystical undertaking. She was later appointed to head prioress of the Sisters House as Sister Marcella but after fourteen years she returned to her family with complete reconciliation. Realizing that frontier farming without a laboring wife created immense difficulties, Christopher took his son and returned to Germantown. He purchased several acres of land and erected a large 60x60 house where he began making clocks, along with a variety of other minor trades. Later, he would enthusiastically add printing to his multifaceted business.

POWER OF THE PRESS

Christopher Sauer maintained communication with Ephrata and learned that Beissel had been forced to give his work to English printers who did not understand the nuances of the German language or culture, especially Benjamin Franklin who loathed Germans and disdainfully called them "Dutch." Realizing an entrepreneurial opportunity, Sauer acquired a press from an unknown benefactor and solicited Ephrata for work. Philadelphia also generated income for the Sauers through the printing of school text-books, almanacs, newspapers, and hymnals. In 1743, this father and son team printed the first European language Bible in America (German), in 1763 the first Bible printed on paper that had been manufactured in America, and in 1776 they printed the first Bible with type-set that had been manufactured in America. (NOTE: John Eliot’s translation to the Algonquin Indians of 1663 was the first non-English Bible printed in America. The first English Bible was printed in 1782 by Robert Aikens).

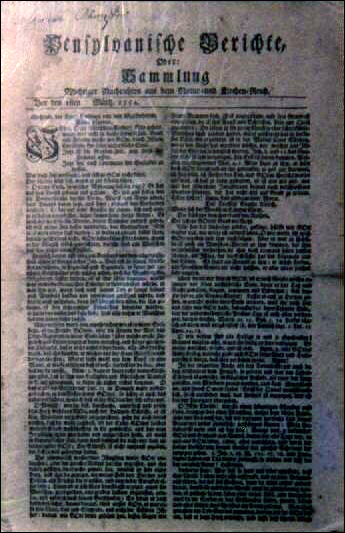

At the height of their success, the Saur team were producing more than two hundred different works in both German and English. This massive publishing enterprise was well known throughout colonial America. It contributed not only to making Germantown a central focus of the many German speaking groups in colonial America, but it also contributed to preserving a cultural bond among the expanding settlements of the German Baptist Brethren. It is claimed that a dedication plaque hung in the shop with these words: “Zur Ehre Gottes und des Nactsten Bestes” (To the glory of God and my neighbor’s good). But this thriving business did not go unnoticed by his chief competitor. Benjamin Franklin sought to curtail the Sauers through his considerable influence in the trade of paper. Sauer and Son responded by acquiring their own paper mill, and further insulated themselves from competition by making their own ink. Sauer felt a personal calling to unite colonial Germans and preserve their ethnicity through the influence of a regular newspaper, which started in 1739 and finally evolved through several name changes to the regular publication of the:

SAUER NEWSPAPER |

HIGH GERMAN

|

PACIFISM AND THE MILITIA

News printed from the Sauer Press became a focal point for German speaking people in America. Measuring about 9 x 13 inches (see above), its two columns per page carried positive news that was informative and uplifting while also serving as a broadside towards political opponents. The Sauers unabashedly sided with the Quaker majority in the Pennsylvania legislature and endeavored to influence elections in order to keep them in power because each held spiritual and temporal views that were largely on common ground. Maintaining a Quaker majority indirectly meant preserving German and Brethren culture. Opposing them were members of the Proprietory Party which largely represented the growing William Penn family, most governors, and related interests. Through the 1740s and 1750s the Sauer Press was instrumental in maintaining a pacifist friendly legislature, but persistent Indian uprisings finally resulted in the election of pro-militia forces from which the Quaker party never recovered. One of the most principal issues of conflict was the raising of a militia to quell Indian uprisings. Non-violence or pacifism was a hallmark of Quakerism, but some have suggested that the Sauers were also motivated by a sense of fairness to Native-Americans. Their lands were being purchased and they were not being paid by the government as promised. Additionally, roaming cattle were trampling the crops of the Indians, and they protested that it was the responsibility of the English to fence their own property. Toleration of colonial expansion reached the boiling point in April of 1763 when the Ottawa chief Pontiac and a loosely united tribal confederacy seemed to appear out of no where and almost succeeded in reclaiming much of the Ohio Valley. Causing a stir from Detroit to Pittsburgh, Native-American warriors captured most of the Allegheny forts with the exception of Fort Pitt. After several months of warfare and the deaths of many significant chiefs, Pontiac finally capitulated in October. Pacifism was becoming an unpopular cause.

CHARITY SCHOOL MOVEMENT

Another issue which deepened the rift between the Sauers and the legislative opposition was the strategy of creating schools to teach Germans the English language, and thereby initiate a policy of their long-term acculturation. It was a very subtle ploy of helping Germans, carefully disguised as a means of removing non-English political opposition. During the 1750’s, there were very few schools in colonial America and attendance was not universally required until the next century. Schools for teaching German children were even fewer. Benjamin Franklin stated: "Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a Colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanicize us instead of our Anglifying them." (Longenecker, 79) Trustees were established to administer the project but it was clear from the beginning that something was terribly amiss. None of the Germanic sects were included in the process! The teachers were all to be English and catechisms were to be offered. Mennonites, Moravians, and Brethren soon became rightfully suspicious of a government cooperating with church leaders to regulate their affairs. It was this kind of opposition that Brethren had experienced in Europe and intended to escape by coming to America. Christopher Sauer was the principal spokesman for the Germans and unleashed an unabated literary assault on the project. He exposed the real nationalistic intentions of the trustees and the Proprietors. In less than a decade, the Charity School movement was idle in the water, and by 1770 it had sunk to the bottom. Sauer had won.

As internal political issues became more tame, the aging Sauer devoted himself to more humanitarian issues, especially the continued deteriorating treatment of Indians. He believed that Native-Americans could never expect fair treatment from a society that preferred their removal. He was prophetically too correct. The last group of Conestoga Indians were massacred by a group of ruffians (the Paxtons) in a Lancaster jail where they were being held for their own protection. Sauer never gave up his fight for the disadvantaged. At the gracious age of sixty-four, Christopher Sauer I died peaceably in 1758.

Christopher Sauer II preserved the rich heritage of his father’s business as well as his religious values. He enlarged the printing business of his father and enlarged the hearts of the Germantown congregation. He eventually became a deacon, minister, and elder. He married Catherine Sharpnack and together they raised nine children. The family grew in size and prominence. During the revolt with Britain, the Pennsylvania Legislature required all citizens to renounce the King of England and vow allegiance to the Commonwealth. The Brethren made no secret of their disdain for oaths and they firmly resisted war and violence in all forms. Sauer II was declared an "enemy of the state" and ordered to appear before a magistrate. However, two weeks before his scheduled appearance, soldiers arrested him at home on May 25, 1778 and placed him in jail after confiscating his property. The following account is Sauers own recollection of the events and quoted directly from A History of the German Baptist Brethren." (Brumbaugh, 416-417).

"...in my house that night and the next day till ten o'clock at night, when a strong party of Captain McClean’s Company surrounded my house and fetched me out of my bed. It was a dark night. They led me through the Indian corn fields, where I could not come along as fast as they wanted me to go. They frequently struck me in the back with their bayonets till they brought me to Bastians Miller’s barn, where they kept me till next morning. Then they striped me naked to the skin and gave me an old shirt and breeches so much torn that I could hardly cover my private parts, then cut my beard and hair, and painted me with oil colors red and black, and so led me along barefooted and bareheaded in a very hot sunshiny day..."

...God moved the heart of the most generous General Muhlenberg to come to me and enquire into my affairs, and promised that he would speak to General Washington and procure me a hearing...I was permitted to go out of the Provo on the 29th day of May; but, as I was not free to take the oath of the States, I was not permitted to go hence to Germantown..."

Military authorities would later sell his estate, business equipment, and household items. He was shamed and disgraced. A few years later, he would peacefully die in the company of two family members; a poor man of this world but a rich man of the next. Since the pacifistic convictions of the Brethren and the Quakers regarding involvement in war and the taking of oaths was no secret to governmental officials, one might ask these obvious questions: Why did the authorities subject him to such extreme disgrace? Why was he arrested two full weeks before a scheduled hearing? Why the haste to sell his property? Granted, others were punished for not swearing allegiance to the Commonwealth but why did Sauer experience such brutal treatment? Why was he denied an opportunity to appeal? Perhaps the matter had racial overtones since Benjamin Franklin (and others) did not obscure his hatred of Germans, calling them "Palatine Boors." Some historians suggest that the real issue was not Sauer’s convictions, but his wealth, his ethnicity, and especially the lingering sting of his fathers political successes against the Proprietary Party interests. It was pay-back time. This father and son enterprise had achieved a modest fortune and social prominence. Their business was very competitive, especially with Franklin. Additionally, the persistent refusal of Sauer II to swear an oath of allegiance to the Independence movement and likewise repudiate the British gave him the appearance of a Loyalist. His sons, Christopher III and Peter were unabashed Loyalists who even offered translation services to the British. Incorporate these factors with Christopher II temporarily moving from the fringes of Germantown to the British controlled inner city of Philadelphia in October, 1777, and it gives the appearance of a Loyalist. Christopher Sauer II was removed as a threat to these interests but the final judgement of his life’s service will rest with a heavenly Judge.

Taking of oaths was strictly forbidden among the early Brethren because of their understanding of the clear, unambiguous statements of Christ in places such as Matthew 5:34-37: “But I say unto you, Swear not at all; neither by heaven; for it is God’s throne: Nor by the earth; for it is his footstool: neither by Jerusalem; for it is the city of the great King. Neither shalt thou swear by thy head, because thou canst not make one hair white or black. But let your communication be, Yea, yea; Nay, nay: for whatsoever is more than these cometh of evil.” Although questions remain as to whether Sauer I ever really joined the Brethren, Sauer II did and paid the price for following his Brethren convictions.

he Germantown Church was also a missionary church, and they regularly sent missionaries into German settlements; west into the Conestoga (Lancaster) and south into Maryland. Just over forty miles up the Schuylkill River near modern Pottstown, the second Brethren congregation was founded as a group of nine believers on November 7, 1724, presumably at the home of Martin Urner who lived in the northern Coventry region of Chester County. He was one of the original Christmas Day Seven who were baptized in the Wissahickon Creek the previous year. Urner joined his baptizer Peter Becker on several missionary expeditions and later journeyed extensively for the Lord on his own. A prosperous farmer turned preacher, Urner was a keen organizer, gentle in manners, yet possessing the capability of dynamic oratory. Alexander Mack, Sr. ordained him to the office of bishop. Coventry grew under the leadership of Martin Urner and soon it became a larger congregation than Germantown. It was also a strong missionary congregation which spawned members to other parts of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. As the original European leadership began to pass away, God raised up new figureheads that would guide and nurture the Brethren. Martin Urner was such a person. His spiritual influence among the numerous congregations is easily underestimated. He frequently visited Brethren churches and helped to maintain a spirit of fellowship and harmony. He preached revival meetings as distant as the Cumberland Valley, performed numerous baptisms, and later guided the Brethren into a new type of discerning assembly, the Annual Meeting. Urner eventually became the most significant Brethren personage of his time.

he Germantown Church was also a missionary church, and they regularly sent missionaries into German settlements; west into the Conestoga (Lancaster) and south into Maryland. Just over forty miles up the Schuylkill River near modern Pottstown, the second Brethren congregation was founded as a group of nine believers on November 7, 1724, presumably at the home of Martin Urner who lived in the northern Coventry region of Chester County. He was one of the original Christmas Day Seven who were baptized in the Wissahickon Creek the previous year. Urner joined his baptizer Peter Becker on several missionary expeditions and later journeyed extensively for the Lord on his own. A prosperous farmer turned preacher, Urner was a keen organizer, gentle in manners, yet possessing the capability of dynamic oratory. Alexander Mack, Sr. ordained him to the office of bishop. Coventry grew under the leadership of Martin Urner and soon it became a larger congregation than Germantown. It was also a strong missionary congregation which spawned members to other parts of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. As the original European leadership began to pass away, God raised up new figureheads that would guide and nurture the Brethren. Martin Urner was such a person. His spiritual influence among the numerous congregations is easily underestimated. He frequently visited Brethren churches and helped to maintain a spirit of fellowship and harmony. He preached revival meetings as distant as the Cumberland Valley, performed numerous baptisms, and later guided the Brethren into a new type of discerning assembly, the Annual Meeting. Urner eventually became the most significant Brethren personage of his time.

COVENTRY: FIRST DAUGHTER CHURCH

Martin Urner was the first guiding light of Coventry, and it is the oldest, continuously active congregation in the Church of the Brethren. Urner was a successful guardian of his flock at Coventry, but it was not very far from the proselytizing activities of Conrad Beissel at Ephrata. Beissel enjoyed the advantage of weak communication between the widely dispersed Brethren settlements, and used his affiliation to literally raid their congregations for his opportunistic enterprise. He would travel among the settlements, converting and baptizing souls with the idea of luring them to Ephrata and Urner firmly opposed him at Coventry. Married women seemed to be a frequent target of Beissel’s missionary excursions. Maria Sauer was enticed from her family to live at Ephrata, the Elder’s wife at Falckner’s Swamp left her husband who forcibly took her back several times, and historians claim that Martin Urner begged his wife to remain faithful, to which she apparently did. During the 1740’s, an intense administrative struggle took place between Israel Eckerlin (Prior) and Conrad Beissel at Ephrata Cloister which gradually became public and bitter. It is often in the heat of confrontation that true character emerges, and when Beissel’s inner nature became evident, many were disillusioned while others felt their suspicions confirmed. Many Brethren returned to their former congregation. As troubles persisted at Ephrata and membership began to diminish, Coventry experienced growth and increased in prominence under the leadership of Urner. Meeting houses were built in 1772, 1817, and 1890. His gift of foresight and organizational skill was especially manifested in his calling for a general meeting of the Brethren.

Early Brethren congregations tended to be small and autonomous, with infrequent visitations by elders that helped to preserve harmony and unity. Because of this infrastructure of small dispersed communities, lacking frequent interaction from outside their German sub-culture, no compelling reason existed for the Brethren to periodically meet in a large delegated body for purposes of deciding universal policy or refining doctrinal understandings. This was about to change with the arrival of the Moravian leader Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf from Czech/Bohemia in 1741. He was especially desirous of uniting all German sects under one parent organization, and convened synods to homogenize individual characteristics among the different groups, and layout an institutional framework.

Brethren attended these conferences, but soon came away with fears of losing their unique identity, especially upon observing several converts being baptized through sprinkling. Keenly reminded of the cost of their Anabaptist heritage by immersion, they perceived Zinzendorf’s effort as a stratagem to return the spiritually naive to infant-baptism, under the very ecclesiastical order from which they had previously fled. From this experience, several Brethren leaders saw the need for a delegated meeting of their own, in order to establish and maintain a uniform observance of their beliefs. In 1742, Martin Urner and George Adam Martin convened the first such Meeting (now called Annual Conference). This meeting was first held at Coventry, principally to reaffirm the Brethren observance of adult baptism by trine immersion. Thus, it was a reaction to outward forces rather than a response to an inner denominational need. These meetings were not convened on an annual schedule for another thirty years.

Returning to the ministry after being disillusioned by the Hacker controversy at Krefeld, Germany, John Naas and four other leaders (Anthony Dierdorf, Jacob More, Rudolph Harley, and John Peter Laushe) left Germantown in 1733 to cross the Delaware River and settle near Amwell, New Jersey. Described as the gentle giant, Naas was pastoring the Krefeld congregation, but grew inactive in the ministry following the Hacker affair. Now at Germantown, Alexander Mack invigorated him and rekindled a passion for missionary zeal. Brethren historian Abraham Cassel states: "During his life time this church was the spiritual birthplace of more Brethren than perhaps any other in the Union" (History of the Church of the Brethren - Eastern Pennsylvania). John Naas was not only tall in stature but also in character. These were years when integrity was a lifestyle. Before his death in 1741, his gracious spirit and gentle demeanor left an indelible mark of Christlikeness on those who came to know him. Once again the fire of evangelism drove him to preach as he had done so profoundly at Krefeld, and missionary zeal often took him back over the Delaware River into Pennsylvania. Many other Amwell preachers developed this same passion for evangelism and continued in Naas' footsteps, a giant legacy to their spiritual mentor. For a period of time, older Brethren in this community would musingly tell youngsters: "There’s a giant buried in that cemetery!"

ollowing the death of Alexander Mack in 1735, there was a gradual exodus from many Brethren settlements to the Cloister at Ephrata. In the wake of Mack’s founding-father influence, Conrad Beissel achieved prominence in leadership and

embarked on a steady course of proselytizing. Alexander Mack, Jr. later came to Ephrata Cloister seeking emotional consolation from the death of his father, only to find bitterness and strife in open display. The previously mentioned administrative war between Eckerlin and Beissel was now in full swing. Hoping for peace and the very preservation of the Ephrata community, Alexander Mack, Jr., Israel and Samuel Eckerlin decided to leave for the Wilderness (see below). This consortium would leave a trail of Brethren settlements and congregations in western Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia. John Mack, another son of founder

Alexander Mack, Sr. and brother of Alexander Mack, Jr., settled for a period of time in Waynesboro, Pennsylvania, and his descendants would later move farther west into an area known as Morrison’s Cove.

ollowing the death of Alexander Mack in 1735, there was a gradual exodus from many Brethren settlements to the Cloister at Ephrata. In the wake of Mack’s founding-father influence, Conrad Beissel achieved prominence in leadership and

embarked on a steady course of proselytizing. Alexander Mack, Jr. later came to Ephrata Cloister seeking emotional consolation from the death of his father, only to find bitterness and strife in open display. The previously mentioned administrative war between Eckerlin and Beissel was now in full swing. Hoping for peace and the very preservation of the Ephrata community, Alexander Mack, Jr., Israel and Samuel Eckerlin decided to leave for the Wilderness (see below). This consortium would leave a trail of Brethren settlements and congregations in western Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia. John Mack, another son of founder

Alexander Mack, Sr. and brother of Alexander Mack, Jr., settled for a period of time in Waynesboro, Pennsylvania, and his descendants would later move farther west into an area known as Morrison’s Cove.

This wide valley of rich fields and streams nestled between rolling mountains is to western Pennsylvania what the Shenandoah is to Virginia. It was here that the name Mack would eventually change to Mock in some family lines, as the Dunkards (see also Brethren Groups) heavily populated it’s farms and churches. Elizabeth Mack, daughter of William Mack (son of Alexander, Mack, Jr.), and great granddaughter of Alexander Mack, Sr., married John Holsinger of Franklin County. Leaving the Waynesboro area, they settled on a large farm near Baker’s Summit in Morrison’s Cove where many present residents claim them as ancestors. Two Brethren congregations in the area would bear the name Holsinger; one in the Cove, organized in 1850 and another beyond the Dunnings and Allegeny Mountains in Bedford County; in a very narrow valley which is called Dunkard Hollow to this day. Mock families began moving south into Bedford County and founded new churches. One of the first being the small country Mock Church, named after Christian Mock. It was constructed by Brethren in the rolling hills near Pleasantville (Alum Bank) in 1843. Before the wide acceptance of Sunday School within the morning service, worship may extend as long as two and occasionally nearly to three hours. Behind the modest pulpit was a long bench accommodating Several Ministers, each taking their appointed time for delivering their sometimes lengthy sermon. Free ministry was the norm before the advent of professional salaried pastors. Having several minsters in each church provided the advantage of caring for more people within the congregation. At least one Elder moderated the various duties and expectations of the local assembly.

Unattended for many years, in the latter part of this century and slowly decaying, it’s rugged log-cabin appearance was restored by local Brethren to its former rustic, Dunkard appearance, along with fresh landscaping to the adjacent cemetery. When asked the question, “Is there anyone still a member of the Church of the Brethren whose name is Mack?“ Genealogists confidently reply “Yes, in Morrison’s Cove.” “Is there any relationship between the Alexander Mack families and the well known Mack Truck Company?” Probably very distant, if at all.

uring the early colonial period, western expansion was limited to infrequent adventures of rugged pioneers and trappers. Indians remained a formidable blockade and they were aided by the French who sought refuge with them from the British during the French and Indian War. Roads in the modern sense of two passable lanes were almost non-existent beyond the narrow two hundred mile wide strip of colonization adjacent to the Atlantic Ocean. The largely uncharted forests to the west were called "The Wilderness" in a similar manner to how Australians refer to the largely uninhabited interior as The Outback. Navigating through the Wilderness on a matrix of crisscrossing Indian paths was difficult and time consuming, for most paths were originally constructed for purposes of hunting, not with the idea of transporting large groups of individuals and property. When the Americans won the Revolutionary War, the unaligned French were gradually dispatched from these strongholds, and most Indian tribes, in spite of localized raids and massacres, became too loosely confederated to present any substantial threat. Western migration started as a trickle with buckskin clad pioneers widening many paths just enough to create pack trails, with straggling bands of trappers contributing to the venture by tossing stones and clearing brush. Since finances and manpower were both lacking, the process of further developing these trails to accommodate wagons was very slow. Organized military excursions vastly improved some roads, but these marches were infrequent and directions often had strategic outcomes in mind, rather than targeting the easiest or smoothest route in getting there. When the army cut a road of their own through new territory, it was usually on the highest ground possible, to ensure against surprise ambushes during future marches - just the very route that would be the most difficult for ordinary folk with heavy wagons. Many of these roads were later rerouted along flatter land. When paths gradually became roads capable of even the smallest wagons, a steady procession of farmers and craftsmen emigrated west and south. Horses could move faster, but oxen were the choice for travelling long distances. A team of oxen moved no faster than a human shuffle, but they ate much less than horses and endured the pace so very much longer. Many of these woodland trails still exist as deeply worn ruts that testify to the accumulative weight of many footsteps.

uring the early colonial period, western expansion was limited to infrequent adventures of rugged pioneers and trappers. Indians remained a formidable blockade and they were aided by the French who sought refuge with them from the British during the French and Indian War. Roads in the modern sense of two passable lanes were almost non-existent beyond the narrow two hundred mile wide strip of colonization adjacent to the Atlantic Ocean. The largely uncharted forests to the west were called "The Wilderness" in a similar manner to how Australians refer to the largely uninhabited interior as The Outback. Navigating through the Wilderness on a matrix of crisscrossing Indian paths was difficult and time consuming, for most paths were originally constructed for purposes of hunting, not with the idea of transporting large groups of individuals and property. When the Americans won the Revolutionary War, the unaligned French were gradually dispatched from these strongholds, and most Indian tribes, in spite of localized raids and massacres, became too loosely confederated to present any substantial threat. Western migration started as a trickle with buckskin clad pioneers widening many paths just enough to create pack trails, with straggling bands of trappers contributing to the venture by tossing stones and clearing brush. Since finances and manpower were both lacking, the process of further developing these trails to accommodate wagons was very slow. Organized military excursions vastly improved some roads, but these marches were infrequent and directions often had strategic outcomes in mind, rather than targeting the easiest or smoothest route in getting there. When the army cut a road of their own through new territory, it was usually on the highest ground possible, to ensure against surprise ambushes during future marches - just the very route that would be the most difficult for ordinary folk with heavy wagons. Many of these roads were later rerouted along flatter land. When paths gradually became roads capable of even the smallest wagons, a steady procession of farmers and craftsmen emigrated west and south. Horses could move faster, but oxen were the choice for travelling long distances. A team of oxen moved no faster than a human shuffle, but they ate much less than horses and endured the pace so very much longer. Many of these woodland trails still exist as deeply worn ruts that testify to the accumulative weight of many footsteps.

Germans had settled in north-western Virginia as early as 1614. Others soon followed in the early 1700’s, moving farther south toward the Blue Ridge Mountain near the wide Shenandoah, because this area was more secure than territory to the west. The French and Indian Wars (1689-1763) allied both groups against their mutual enemy, the British colonists. Migration was difficult until after the end of the Revolutionary War, at which time westward expansion gradually increased. German groups in Virginia maintained connections with their friends in Philadelphia through paths touching Lancaster, York, and Franklin Counties, and then south toward Fredricksburg, and the Potomac River. Because Pennsylvania required an oath of allegiance during the Revolutionary War, peace conscious Brethren moved to Virginia where land was cheap and local government flaccid. Following their departure from Ephrata, Alexander Mack, Jr. and the Eckerlin brothers had previously established several Brethren settlements in Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia (not a separate state until 1863). Subsequent migrations would yield a strong German presence in the area which accelerated the movement of Brethren from Pennsylvania into Virginia and the Carolinas, but the Wilderness to the west remained a barrier. Although never as heavily populated as in the North, the southern states experienced a slow, but steady migration of Brethren families.

Daniel Boone (1734-1820) was born near Reading, Pennsylvania to a Quaker father who had married a German women with Brethren affiliation. Squire Boone and Sarah Morgan marry in the Friends' meetinghouse in Gwynedd, Pennsylvania, and relocate in 1731 to the upper Schuylkill River valley where Daniel is born near Reading. It is traditionally believed, although undocumented, that the children grew up in the Dunkard faith with a heavy influence of Quakerism. After moving through Virginia and settling in North Carolina, Daniel Boone was contracted by the Transylvania Company to establish a road by which colonists may travel into Kentucky and beyond. On an extended hunting trip with friends over the Cumberland Mountains in 1769, Boone found a route through a gap which came to be known as the Cumberland Gap. With a party of thirty men, Boone constructed a nearly 300 mile passage, aptly called the "Wilderness Road." Until the middle of the next century, almost 100,000 pioneers would migrate into the new territories of Kentucky, western Tennessee, and Ohio. In the early 1800’s, many Brethren families chose to move west into Ohio and Indiana, either through the Cumberland Gap and establishing congregations along the Ohio River to the east of Cincinnati, or overland by wagon from Pittsburgh to settle northeast of Columbus. The first German Baptist Brethren congregation organized in Ohio was Stonelick (1795), and Four Mile (1809) the first in Indiana. By the middle of the Nineteenth Century, several Brethren congregations had been planted and organized into state districts. Families also moved south

John Kline (1797-1864) was a traveling preacher, church Elder, and later moderator of Annual Conference. Returning home from the blacksmith shop, he was tragically shot while riding horseback, presumably by individuals who believed that his traveling great distances was for spying instead of preaching. During this period of the Civil War, he traveled extensively through Virginia, Maryland, Ohio, and Indiana.

Two major arteries for westward migration during the Nineteenth Century were the Ohio River in first half and the railroad in the latter half. Flatboat portage on the Ohio River from Pittsburgh contributed to faster transportation, and explains why most Brethren first entered the states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois from the south. River traffic greatly hastened Brethren expansion for a predominately foot-path culture, and the railroad propelled them even further. Short-run railroad lines began appearing in the U.S. during the 1840s. Improvements in railroading included sleeping cars (1856) and the use of steel rather than wrought iron rails (circa, 1863). Railroad construction achieved a historic landmark with the completion of the first transcontinental railway, when the westward building Union Pacific met the eastward building Central Pacific on May 10, 1869 at Promontory Point, Utah. Varying track widths were standardized in the mid-1880’s at 4' 8 1/2", and this vastly increased the speed of rail traffic because passengers no longer needed to wait for switching trains. Annual Meeting (Conference) was first held in the mid-west near Waddams Grove, Stephenson County, Illinois in 1856. With speedy rail travel, no barriers remained to impede Brethren from reaching and settling the west coast from California to Washington.

The expansion of the Brethren during the Nineteenth Century deposited them in different geographical regions and cultures of the United States, requiring them to reconsider their own culture and belief system. Formerly agriculturally based and ethnically German, the Brethren now included a growing urbanite population, a socially diverse membership, plus a noticeable increase of the usage of English. This acculturation of some Brethren and the steadfastness of many others drew lines of confrontation between more conservative thinking and new progressive innovation. This century witnessed the Brethren coming to terms with these varying influences.

Photo Credits:

- Germantown Meeting House: Color by Ronald J. Gordon

- Germantown Meeting House: Black & White permission from Brethren Historical Archives

- Pensylvanische Berichte: Sauer Newspaper by Ronald J. Gordon (on display at Germantown)

- Wissahickon Creek scenes by Ronald J. Gordon and Ralph Hanawalt

Literary Resources:

- Martin Brumbaugh, A History Of The German Baptist Brethren, Brethren Publishing, 1899

- Donald Durnbaugh, Fruit of the Vine, Brethren Press, 1997

- Stephen Longenecker, The Christopher Sauers, Brethren Press, 1981

- Floyd Mallot, Studies in Brethren History, Brethren Publishing, 1954

Migration Resources:

- Wilderness Road - Philadelphia, PA to Lexington, KY

- Cumberland Gap National Park

- Brethren Life by Merle C. Rummel

- Boone Family

- Braddock Road

- Brethren Frontiers

- Brethren Migrations

- Great Warrior’s Path

- Kanawha Trace

- Michigan Road

- The Ohio Frontier

- Westward Migration

- Wilderness Road

Genealogy Information:

- Durnbaugh - Passenger List of the Ship “Allen” (Mack party to America)

- Members of Germantown Congregation

- Members of the Coventry Congregation

- Ministers in the Coventry Congregation

- Members of the Conestoga Congregation

- Baptisms performed by Elder Christopher Sauer

- Baptisms performed by Elder Martin Urner

- Baptisms performed by Elder Alexander Mack

- Genealogy of the Urner Family and sketch of the Coventry Brethren

“Now he that planteth and he that watereth are one; and every man shall receive his own reward

according to his own labour. For we are labourers together with God.”

1 Corinthians 3:8,9

SAILING SHIP

SAILING SHIP HISTORICAL MARKER

HISTORICAL MARKER WISSAHICKON CREEK

WISSAHICKON CREEK ORIGINAL 1770 STRUCTURE

ORIGINAL 1770 STRUCTURE REAR ADDITION OF 1897

REAR ADDITION OF 1897 RIGHT EXTENSION OF 1915

RIGHT EXTENSION OF 1915 GOOGLE EARTH AERIAL

GOOGLE EARTH AERIAL

MOCK CHURCH OUTSIDE

MOCK CHURCH OUTSIDE MOCK CHURCH INSIDE

MOCK CHURCH INSIDE WILDERNESS ROAD

WILDERNESS ROAD