Anabaptism in 16th Century Europe

Written by Ronald J. Gordon ~ Published April, 1998 ~ Last Updated: June, 2022 ©

This document may be reproduced for non-profit or educational purposes only, with the

provisions that the entire document remain intact and full acknowledgement be given to the author.

It has been extracted from the European Origin of the Church of the Brethren.

The Short Answer: A movement that repudiated ecclesiastical control of individuals through infant baptism and sacramentalism, and strived to attain radical discipleship to Christ by separation from worldly enticements. ANA (Greek, “again”) + Baptists made a public statement through the act of rebaptizing - theological (to believers) and political (to authorities). Their illegal rebaptisms were perceived by the government as subversive and a genuine threat to civil stability. Anabaptists were routinely hunted by Täufenjager (baptist hunters) and executed through drownings (mockingly called the third baptism) and as human torches. Few of the original leaders escaped martyrdom. |

Challenge to the Reformers

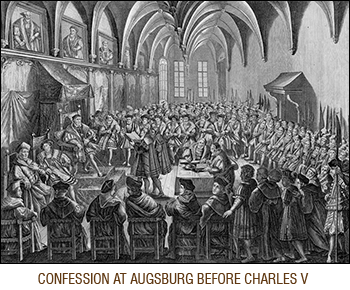

he enthusiasm of the Reformers was finally given vent for expression at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, when the Emperor Charles V required a formal presentation of specific justifications surrounding the the activities of Martin Luther. Pope Leo X had excommunicated Luther in January of 1521 and Charles declared him an outlaw the following May. But in just nine brief years the political and religious stage of Europe had been greatly rearranged. Central Europe was slowly becoming a tempestuous sea of conflict. The Ottoman Turks had successfully invaded most of the eastern territories and stood ready to overthrow the city of Vienna. To face this situation, Charles desperately needed the support of a united Empire that was weakening from growing religious and political fragmentation. Luther was invited to the Imperial Diet but could not attend since he was technically still an outlaw. Philipp Melanchthon, his comrade and fellow professor in theology at Wittenberg, brilliantly articulated the justifications for reform in a Confession that was delivered before the Emperor by Christian Beyer, the chancellor of Saxony. So masterfully did Melanchthon define the basic articles of faith undergirding reform that Lutherans still regard the Augsburg Confession as one of their primary declarations of faith. Enthusiasm for reform was not limited to Germany, for just a few years after Luther posted his church door arguments, Ulrich Zwingli had found himself in trouble with a Catholic bishop in Zurich, Switzerland, over matters pertaining to the observance of Lent. He had previously started a small cultural study group of several men, especially including Conrad Grebel and Felix Mantz, but their focus gradually turned more to biblical matters. Each was proficiently skilled in Latin, Hebrew, and Greek; and they concluded from a scrupulous examination of the New Testament that infant baptism was scripturally groundless, because only an adult with a mature comprehension of their decision should receive baptism. After corresponding with Luther on numerous issues, he gradually decided in 1522 to leave the priesthood. Zwingli believed that ultimate authority in the church belongs in the local community of believers, not a distant ecclesiastical body. In the Disputations of 1523, Zwingli sought to become responsible under the cantonical government, which was a distinct signal of his break with Rome. Subsequently, the city of Zurich removed themselves from Papal authority to become an evangelical city. Grebel and Mantz were passionate about reform and wanted to actively pursue their new conclusions, but Zwingli protested that it would incite an uproar and he gradually began to distance himself from them. Three years later, in January of 1525, Zwingli disputed his former companions before the Great Council of Zurich, in which the Council sided with him and declared Grebel and Mantz to be radicals. Nevertheless, they were not deterred from pursuing their convictions, and they soon gained the companionship of Georg Blaurock, a priest who shared their theological views, and likewise eschewed the power of Rome. During one of their meetings involving a spirited discussion of believer's baptism, Blaurock requested to be re-baptized since he was first baptized as an infant. Grebel baptized him, and Blaurock, in turn, baptized Grebel and Mantz. Anabaptism was formally born on January 21, 1525. Additionally, it should be noted that Conrad Grebel was a lay person - not an ordained priest, minister, or the holder of an important ecclesiastical office. This is an interesting departure from the normal caste of the Reformers.

he enthusiasm of the Reformers was finally given vent for expression at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, when the Emperor Charles V required a formal presentation of specific justifications surrounding the the activities of Martin Luther. Pope Leo X had excommunicated Luther in January of 1521 and Charles declared him an outlaw the following May. But in just nine brief years the political and religious stage of Europe had been greatly rearranged. Central Europe was slowly becoming a tempestuous sea of conflict. The Ottoman Turks had successfully invaded most of the eastern territories and stood ready to overthrow the city of Vienna. To face this situation, Charles desperately needed the support of a united Empire that was weakening from growing religious and political fragmentation. Luther was invited to the Imperial Diet but could not attend since he was technically still an outlaw. Philipp Melanchthon, his comrade and fellow professor in theology at Wittenberg, brilliantly articulated the justifications for reform in a Confession that was delivered before the Emperor by Christian Beyer, the chancellor of Saxony. So masterfully did Melanchthon define the basic articles of faith undergirding reform that Lutherans still regard the Augsburg Confession as one of their primary declarations of faith. Enthusiasm for reform was not limited to Germany, for just a few years after Luther posted his church door arguments, Ulrich Zwingli had found himself in trouble with a Catholic bishop in Zurich, Switzerland, over matters pertaining to the observance of Lent. He had previously started a small cultural study group of several men, especially including Conrad Grebel and Felix Mantz, but their focus gradually turned more to biblical matters. Each was proficiently skilled in Latin, Hebrew, and Greek; and they concluded from a scrupulous examination of the New Testament that infant baptism was scripturally groundless, because only an adult with a mature comprehension of their decision should receive baptism. After corresponding with Luther on numerous issues, he gradually decided in 1522 to leave the priesthood. Zwingli believed that ultimate authority in the church belongs in the local community of believers, not a distant ecclesiastical body. In the Disputations of 1523, Zwingli sought to become responsible under the cantonical government, which was a distinct signal of his break with Rome. Subsequently, the city of Zurich removed themselves from Papal authority to become an evangelical city. Grebel and Mantz were passionate about reform and wanted to actively pursue their new conclusions, but Zwingli protested that it would incite an uproar and he gradually began to distance himself from them. Three years later, in January of 1525, Zwingli disputed his former companions before the Great Council of Zurich, in which the Council sided with him and declared Grebel and Mantz to be radicals. Nevertheless, they were not deterred from pursuing their convictions, and they soon gained the companionship of Georg Blaurock, a priest who shared their theological views, and likewise eschewed the power of Rome. During one of their meetings involving a spirited discussion of believer's baptism, Blaurock requested to be re-baptized since he was first baptized as an infant. Grebel baptized him, and Blaurock, in turn, baptized Grebel and Mantz. Anabaptism was formally born on January 21, 1525. Additionally, it should be noted that Conrad Grebel was a lay person - not an ordained priest, minister, or the holder of an important ecclesiastical office. This is an interesting departure from the normal caste of the Reformers.

Others soon joined their company and adult re-baptism or ANA (Greek for 'again') + BAPTISM was born, since each follower was initially baptized as an infant.. Resistance from the state was immediate with Felix Mantz being executed by drowning at Zurich, and fellow companion Wolfgang Uliman along with others were burned at the stake in Waldsee. Zwingli turned from the movement and began to write and teach with zeal, bordering on fanaticism, that Anabaptism was false and intolerable. He later imprisoned Anabaptists in the tower of Zurich, allowing men and women to die until the last, enduring the stench as their dead were not removed from among them. As the early church thrived during periods of state persecution, so also would Anabaptism grow and spread throughout Europe. An old truth was being validated once again; Turmoil from without spreads a movement while turmoil from within destroys it. Protestant refugees would soon find a haven in the independent French Swiss city of Geneva where Jean Cauvin, known better in the Latin form of Calvin would soon turn Geneva into a Protestant Rome. He was educated as a lawyer and created a faith system with logic that gave it strong conviction. The rigor and depth of Calvinism would spread as far as Scotland where it was promulgated by the illustrious preacher and organizer John Knox.

These dedicated recipients of persecution and death from the European church-state alliance of the Catholic and Lutheran churches were the most resolute product of the Reformation. They did not pause with Luther or Calvin, but sought to change the dual hand of church and state forever. No exercise of force in religion was their proclamation. During this time, citizens were forced to belong to the religion of their district, and in times of war or domestic unrest, changes in nobility and their religious disposition could be frequent. Anabaptism was properly a grass-roots movement by disaffected commoners who did not find early leadership in any personage of significant notoriety such as Luther or Calvin. For this reason, Anabaptists did not win intellectual respectability as the larger reform movements whose figureheads were men of education who produced thoughtfully reasoned arguments that were persuasive to thinking minds. Disunited groups of Anabaptists were not privileged with many leaders of academic proficiency, certainly because their fundamental appeal was more to emotional practicality than intellect. Possibly due to the precedent setting activities of the major Reformers who challenged the authority of the Roman Catholic Church with the Bible itself, and especially since Luther translated Holy Writ into German, the scriptures were no longer the exclusive property of bishops. Interpretation now enjoyed a wider audience. The great majority of Anabaptists were peaceful, constructive, and in some ways nearly ascetic. They adhered to strict ethical standards, avoidance of immorality, and fundamentally believed that faith was something to be 'demonstrated' through daily activity. Regretfully due to their social origin and radicalism, they were regarded as extremists and their excesses stayed in the public mind. For example, in the 1530's, one group of Anabaptists under the leadership of John of Leyden gained control of the German city of Munster where they attempted to institute a government that repulsed even the sympathetic. They pushed the doctrine of justification by faith to an extreme form of anarchism, i.e., people determining law according to conscience instead of a written code. The mayhem in Munster disallowed private property, class distinctions, and permitted a few to engage in polygamy. They had disturbed an established order that was astonished at their radical fanaticism and decided to crush them - at any cost.

Anabaptism gave new meaning to spiritual living. It was an intense experience. Opponent of the movement Sebastian Franek wrote in 1531: They soon gained a large following, and baptized thousands, drawing to themselves many sincere souls who had a zeal for God ... They increased so rapidly that the world feared an uprising by them though I have learned that this fear had no justification whatsoever (Chronica, Zeitbuch und Geschichtbibel). Heinrich Bullinger, successor to Zwingli's writes: Anabaptism spread with such speed that there was reason to fear that the majority of the common people would unite with this sect (Augsburgs Reformationsgeschichte). Zwingli himself became so alarmed at the strength of the movement and the heartfelt convictions of it's adherents that he soon considered his own conflicts and theological skirmishes with Catholicism to be child's play (Letter of Zwingli to Vadian, May 28, 1525).

The dual hand of church and state released its severest form of tyranny on the Anabaptists. The Rhine Valley during the mid 1500's witnessed nightly torches of burning saints. They were mocked and scorned by angry crowds as they were led to their executions. It is ironic that the very entity that suffered the initial pain of affliction in the Roman arena now became the Afflicter. Doubly ironic is that many of the Reformers who enjoyed their newly gained freedom from the Roman Catholic Church, likewise chose to be the new Afflicters. The wanton slaughter of Anabaptists was severe, vitriolic, and offered as entertainment in some locations; but still they grew in number, and became even more resolute in their convictions and activities. European nobility pronounced death to all Anabaptists at the Diet of Speyer in 1529, and within a few years most of the original leaders met with violent deaths, but still the movement grew and increased in strength. Täufenjager (baptist hunters) were special groups that systematically and persistently tracked and arrested these intractable saints. History has witnessed few movements whose participants were as inveterate as those of Anabaptism.

New Interpretations

nabaptism introduced a new form of worship service that was distinctly emotional. Whereas liturgical services were historically generous in ritual and pageantry before quiet worshipers, these new services were frequently loud with participants shouting and dancing. Sermons were electrified with hopes of heaven and terrors of hell. It is not over-simplification to describe them as the 'holy rollers' of their day, because the emotional appeal was captivating to passive congregants entirely accustomed to inert solemnity. This was interactive, new - revolutionary. Preaching styles contained energy. Most groups expected Christ's immediate return. Anabaptists gave new interpretations to historic traditions of the church, and invented a few new traditions of their own. Their distrust of government was obvious, and they would not take oaths. A few practiced what can only be described as combative pacifism. In other words, they were willing to respond aggressively in the most vociferous manner without actually becoming physical. One such person was Jacob Hutter who is recognized as the founder of the Hutterites.

nabaptism introduced a new form of worship service that was distinctly emotional. Whereas liturgical services were historically generous in ritual and pageantry before quiet worshipers, these new services were frequently loud with participants shouting and dancing. Sermons were electrified with hopes of heaven and terrors of hell. It is not over-simplification to describe them as the 'holy rollers' of their day, because the emotional appeal was captivating to passive congregants entirely accustomed to inert solemnity. This was interactive, new - revolutionary. Preaching styles contained energy. Most groups expected Christ's immediate return. Anabaptists gave new interpretations to historic traditions of the church, and invented a few new traditions of their own. Their distrust of government was obvious, and they would not take oaths. A few practiced what can only be described as combative pacifism. In other words, they were willing to respond aggressively in the most vociferous manner without actually becoming physical. One such person was Jacob Hutter who is recognized as the founder of the Hutterites.

"Woe, woe! unto you, O ye Moravian rulers, who have sworn to that cruel tyrant and enemy of God's truth, Ferdinand, to drive away his pious and faithful servants. Woe! we say unto you, who fear that frail and mortal man more than the living, omnipotent, and eternal God, and chase from you, suddenly and inhumanly, the children of God, the afflicted widow, the desolate orphan, and scatter them abroad...God, by the mouth of the prophet proclaims that He will fearfully and terribly avenge the shedding of innocent blood, and will not pass by such as fear not to pollute and contaminate their hands therewith. Therefore, great slaughter, much misery and anguish, sorrow and adversity, yea, everlasting groaning, pain and torment are daily appointed you."

J.T. Van Braght, "Martyrology: Letters of Jakob Hutter," Vol I, p. 151-153

R.J. Smithson, "The Anabaptists," London, 1935, p. 69-71

Also see "History of Civilization," Prentice-Hall, 1967, p. 481

The great majority of Anabaptists were quiet and very respectful. Everyday living was peaceful, simple, and demonstrably pious. They emphasized community responsibility and economic egalitarianism. Most were shocked by the activities of their own extremists who over took a city government and tried to run it according to theological principles. Their excessive abuses garnered the appellation: 'Mayhem in Munster,' and unfortunately destined them to bare the stigma of a few radicals. After the systematic execution of most leaders, their most inspirational figurehead was Menno Simons, a Dutch-born Catholic priest and contemporary of Zwingli, Grebel, and Mantz. He had many quiet doubts about church doctrines such as transubstantiation and infant baptism. Following a careful study of the New Testament and Luther's writings, he left the Catholic Church, adhering only to orthodox Christian doctrines and excluding those beliefs not clearly articulated in the New Testament. He strongly opposed the Mayhem in Munster, but was forced to go into hiding for a year because of his offers of minor assistance to them. Simon's followers later became known as Mennonites. Due to its grass-roots origin, Anabaptism would heavily influence religious thought far beyond the century of its birth, including the Schwarzenau Brethren who would rebaptize themselves in the Eder River in 1708. Anabaptist beliefs and practices are so compelling and attractive that it has endured, with minor changes, into the modern era.

- Fallen Church

-

Beginning with Martin Luther and continuing with most of the primary reformers (including the Anabaptists) is the concept of a “fallen church,” where a good and true earthly vessel of God had slipped from its manifest purpose. Abuses of the clergy and the pope were easily exposed, and reform became the vehicle whereby the reformers sought to transport the church back to its original purity. This was another new interpretation. If an entity has fallen, then it logically had a point of time when it began to decline. Interestingly, the date at which each reformer places the moment of its descent is remarkably different. Zwingli opposed the rise and powerful ascendancy of the papacy and saw this as the beginning of the fall. Luther accepted the papal state, but not its abuses. He did not disagree with its administrative structure, only the abuses of power and influence from its leaders. The differences in time lines between the primary reformers was minimal except for the Anabaptists who regarded the fall to have started with the emperor Constantine who married state and church together. This was the commencement of the rise of evil in the church, and the beginning of the fall. Contrariwise, both Luther and Zwingli admired this historical event. It was a crowning achievement for them.

A distinct teaching that came out of the Anabaptist movement is the premise that the church should be an assembly of believers having came through a regenerative experience. They understood the New Testament to clearly teach a process of regeneration; which is, becoming aware of one's sinfulness through the redemptive work of the Holy Spirit, acknowledging the need of rescue from this situation, receiving salvation by grace (unmerited love of God demonstrated through Christ's sacrifice), and continuing spiritual renewal of the mind to become a witness of God's offer of grace. - Church going political

- The earliest form of Christianity describes scattered house fellowships of believers who viewed the state as evil. They boldly served one greater than Caesar, and unapologetically proclaimed Jesus Christ as the Lord of their kingdom. New Testament writers made a clear distinction between the church and the world. Apostle John stated: “Love not the world, neither the things that are in the world. If any man love the world, the love of the Father is not in him” - 1 John 2:15. When the church became espoused to the state under Constantine, the Anabaptists saw an unrelenting series of compromises in principles of faith. Although the Edit of Milan (313) only legalized Christianity, the emperor Theodosius made it the state religion on February 20, 380, and required everyone to be baptized. This meant that all soldiers where now Christians; a new twist for believers who previously desisted military service because of their allegiance to a greater emperor. Anabaptists saw this historical event as the beginning of a spiritually injurious domino effect which progressively compromised spiritual principles - century after century.

- Infant baptism imprison's the individual

- The joy of New Testament baptism through repentance and conversion of adult believers had been lost in this practice which originated in about the Fourth century. Anabaptists reserved their strongest criticism for this practice, because they esteemed it to have repudiated the foundation of salvation by grace. No longer did people have the opportunity to turn from their evil ways and join a community of believers through recognition of their own sinfulness. Their lives and destinies were imprisoned by the Church from near the moment of their birth. Salvation lost its majesty. Grace became only a distant theme. It was no longer a divine particular to be cherished, for it had become a regulated state of existence. For the Anabaptists, a challenge to the Church was equivalent to sacrificing their own eternity. This powerful hold on the soul of a person was a theological road block to understanding and appreciating the very joy of being a Christian. Rebaptizing adult believers was therefore a theological expression, a political statement, an act of dissent, and perhaps the medieval equivalent of burning one's draft card. This analogy is not intended to legitimize draft-card burning nor to denigrate Anabaptist martyrdom, only to illustrate the Severe Cost that is required of those who follow their beliefs with the full knowledge that their actions are in direct opposition to Church State authorities.

- Sacraments become weapons

-

Originally, the church received the Sacraments through a celebratory occasion that remembered the Lord's sacrifice. As the church became political, so did the sacraments. Instead of being symbols of a festive occasion, they were seen as a vehicle for maintaining power over individuals by the church. Persons barred from receiving the Sacraments became persons denied salvation. Objects representing God's love became weapons of manipulation. This was a fundamental change in New Testament doctrine, for Anabaptists believed that upon conversion, people are released from bondage to sin to experience the joy of spiritual freedom that should be celebrated by the church. Infant baptism and sacramental leverage obfuscated the opportunity for freedom, by imprisoning a person under the captivity of an ecclesiastical power.

- Early believers were a 'called out' assembly, originating from the Greek word ekklesia (those called out). Medieval believers were an imprisoned assembly held captive under the bondage of church authority. There was very little opportunity for them to experience a 'calling out,' for administration of the Sacraments was the churches method of keeping them inside and under control.

- Reform means starting over

- Whereas most 16th century reformers understood the word reform to mean that a fallen church structure needed restoration to its original purity, Anabaptists rejected the churches existing structure because they believed that it had become too corrupt. Purity could only be achieved by starting over. It was this concept which invited severe persecution from the State Churches which saw their very existence in jeopardy. Anabaptists were viciously dealt with by the main three church denominations in league with government officials because they were viewed as subversives. Luther and other reformers believed that abuses by the church, such as the temporal authority of the pope or the immoral excesses of the clergy should be corrected while still retaining the historical legacy of the church structure. They viewed themselves as protectors of the historically true church. If medieval church structure may be viewed as a brick wall, Luther wanted to realign and replace those few bricks that would correct the problem yet preserve the integrity of the wall. Anabaptists saw these same bricks as indicative of a foundation that had shifted. Repair meant changing the position of the foundation, no matter what happens to the bricks. Not even mainline reformers could accept the magnitude or the consequences of such radical change.

Radical Departure

n summary, Anabaptism was a new movement that was perceived as a radical departure from the established church, even by other reformers who desired to restore and maintain a fallen structure. In civil matters, Anabaptists rejected public office and would not serve in the military. Their disdain for materialism also brought contempt from a weak but rising middle class that was just discovering primitive capitalism. Persecution from many sides was resolute throughout Europe because nobility, church officials, and merchants viewed Anabaptism as a fundamental threat to their own destinies. Thousands were drowned, tortured or burned at the stake, but martyrdom only fortified their belief that suffering was a touchstone of their genuine faithfulness to true Christianity. Drowning was often employed because authorities thought it a befitting punishment for rebaptizers.

n summary, Anabaptism was a new movement that was perceived as a radical departure from the established church, even by other reformers who desired to restore and maintain a fallen structure. In civil matters, Anabaptists rejected public office and would not serve in the military. Their disdain for materialism also brought contempt from a weak but rising middle class that was just discovering primitive capitalism. Persecution from many sides was resolute throughout Europe because nobility, church officials, and merchants viewed Anabaptism as a fundamental threat to their own destinies. Thousands were drowned, tortured or burned at the stake, but martyrdom only fortified their belief that suffering was a touchstone of their genuine faithfulness to true Christianity. Drowning was often employed because authorities thought it a befitting punishment for rebaptizers.

Anabaptism was both a theological and academic reaction to the church system. Because of its open challenge to both church and secular (church influenced) government, it has been improperly viewed as a political movement. Toleration for this fledgling movement came first in the Netherlands where the Catholic priest Menno Simons had already renounced his allegiance to Rome, but may have retained a closer adherence to the mainstream reform idea of preserving church structure. Other havens gradually appeared when nobles realized that most Anabaptists were hard working farmers and craftsmen who quickly contributed to the local economy. Following the Thirty Years War that left feudal economies in ruin, many were actually invited to settle in the Palatinate district of Germany, in order to rebuild a war stricken landscape. Hutterites also found refuge in Moravia. Numerous attempts were made to formally record a basic consensus of Anabaptism by its followers. The most notable are the Schleitheim Confession of 1527, named after the Swiss-Austrian border city where early leaders seclusively met, and the 1632 Dutch Mennonite Dordrecht Confession, which is principally followed by many Amish. Some intellectual disagreement remains over the full effect of Anabaptism on the Schwarzenau Brethren (later Church of the Brethren), however, a clear imprint of Anabaptism is visible when they initiated their faith community through rebaptism of believing adults.

Modern devotees rarely perform rebaptisms because their children are not first baptized as infants, therefore a re-baptism is not an issue. Youth generally receive baptism and membership when they reach that varying age where they are able to understand and accept the gospel message centered in the teachings of Christ. Anabaptists in the modern era are known for their distinctive beliefs and cultural heritage. With little variance, they stress very closely the same doctrinal positions as their 16th Century advocates, such as, but not limited to:

- Priesthood of all believers

- Separation of Church and State, with laws of God taking precedence

- Voluntary membership, unregulated by the state

- Greater emphasis on the authority of scripture

- Baptism as a sign of a believers commitment

- Non-violence and Non-resistance

- Refusal to bear weapons or engage in military service

- Discipleship being central to understanding the teachings of Jesus Christ

- Separation from sinful and worldly pleasures

They believe intently that believers are to closely adhere to the teachings of Jesus Christ as found in the New Testament, their primary source for developing rules of faith and practice. It is difficult to find a New Testament basis for the killing of another human being since Christ taught: Ye have heard that it hath been said, Thou shalt love thy neighbour, and hate thine enemy. But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you; That ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust - Matthew 5:43-45. Christ himself lived by this teaching. There is no record of Jesus killing anyone or his suggesting that disciples should do such. Instead, he prayed for those who persecuted him and forgave those who were about to crucify him. Pacifism looks upon violent behavior and pleads with us to rise above it.

Additional Resources

- Anabaptist Church

- Anabaptist Story

- Anabaptist: Sixteenth Century Usage

- Anabaptists (Catholic Encyclopedia)

- Anabaptists: Separate By Choice, Marginal By Force

- Bibliography: (Goshen)

- Bibliography for Mennonites

- Christian Ethics from an Anabaptist Perspective

- Commemorating the Anabaptists

- Compassion for the Enemy

- Conrad Grebel College

- Dordrech Confession

- Foxe's Book Of Martyrs

- Martyrs Mirror with Commentary

- Menno Simons (Brief History), (Expanded)

- Münster Rebellion

- New Birth: Menno Simons

- Present at the Inception: Menno Simons and the Beginnings of Dutch Anabaptism

- Radical Reformation: The Anabaptists

- Relevance of Menno Simons for Evangelical Christians

- Schleitheim Confession

- Secret of the Strength: What Would the Anabaptists Tell This Generation?

- The Swiss Brethren: Georg Blaurock, Conrad Grebel, Felix Manz

- What Does It Mean To Be Amish

- Young Center for the Study of Anabaptist and Pietist Groups

- Zurich and Anabaptism

- Zwingli, Ulrich

“For which of you, intending to build a tower, sitteth not down first, and ‘counteth the cost’

whether he have sufficient to finish it?”

Luke 14:28