Apostle Paul and the Winds of Crete

Written by Ronald J. Gordon Published: February, 2016 ~ Last Updated: August, 2021 ©

This document may be reproduced for non-profit or educational purposes only, with the

provisions that this document remain intact and full acknowledgement be given to the author.

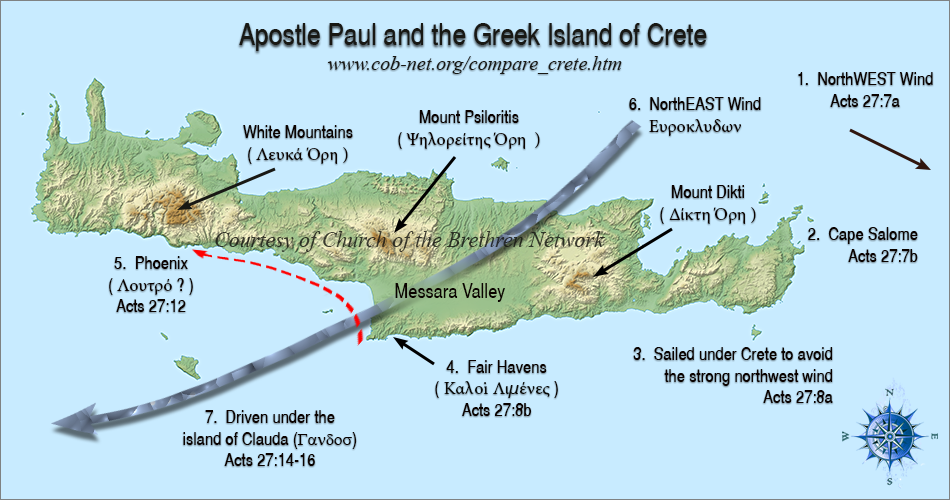

Among biblical commentators and educators, there exists a degree of uncertainty surrounding the voyage of Apostle Paul around the Greek island of Crete, particularly the need to leave the port of Fair Havens, why the ship was docked there in the first place if it was not suitable for winter lodging, why Julius the centurion and the ship owner decided (Acts 27:11) to sail to Phoenix or Phenice on the western coast of the island, and the type of storm that was encountered.

Knowing the geographical makeup of the island will be helpful. Crete is a blend of three principal regions: Lowland Hills to the east, High Mountains to the west, and the central

Messara Valley, a rich illuvial plain filled with orchards and fields of grain. There are five cities on the north coast, built on the remains of ancient Minoan foundations. Most of western Crete is mountainous, stretching from the eight thousand foot

Mount Psiloritis in the central region, to the elongated

White Mountain Range

with towering peaks between six and eight thousand feet. At several locations, ridges from this mountain range extend down to the

Southwest Coastline

providing excellent shelter for vessels pummeled by north or northwest winds. It is here in the western half of the island that the prudent ship captain receives protection from storms, not the eastern half of Crete where most of the coastline is bordered by

Lowland Hills

of only a few hundred feet.

Sailing upon the Mediterranean Sea over the winter months was nearly impossible for square rigged vessels that do not easily tack (zig-zag) into the wind. Vegetius records in the 4th century that sailing in the Mediterranean after September 15th was dangerous and after November 11th was impossible, De Re Militari 4.39. Only certain military vessels of the

Liburnian Class

(propelled by oars) were the exception. Luke states in Acts 27:9 that the “fast” or Day of Atonement was passed, so this would place the beginning of their journey in the “dangerous” period, just before the “impossible” period. Why then was the owner of this grain vessel sailing at this time? One can only speculate that he was trying to squeeze in one last run for the season, since people of the Empire still needed to eat during the winter. The following series of events is suggested as a plausible explanation of the entire Cretan incident.

Traveling, Verse by Verse

- Acts 27:2 - The Cretan story actually begins when their first Adramyttium ship leaves the port of Caesarea where Apostle Paul was held prisoner. This is a coastal maritime ship engaging in commerce, town by town. “We launched, meaning to sail by the coasts of Asia; one Aristarchus, a Macedonian of Thessalonica, being with us.” Italy was apparently not on their list, for Sidon was the first port of call, then Myra in Lycia, at some point Adramyttium on the east side of modern day Turkey, and one passenger is bound for Macedonia. It is most probably a small vessel which the Centurion knows will never withstand the rough seas of the central Mediterranean.

- Acts 27:4,5 - After leaving Sidon, the helmsman steers to the sheltered side of Cyprus and then through the seas of Cilicia and Pamphylia. Since these two nations were to the immediate north of Cyprus, it would be reasonable to conclude that the ship passed between Cyprus to the south (port-side) and the mainland to the north (starboard). Thus, the sheltered side of Cyprus would have been its eastern side, and the prevailing wind would have been coming from the northwest. Contrariwise, if the wind was coming from the west, they would have experienced incredible difficulty in reaching their destination of Myra (modern Demre), if even possible at all for a larger vessel.

- Acts 27:6 - In Myra the Centurion acquires passage on an

Alexandrian Grain Ship

bound for Italy to supply food to the Roman Empire. Vast harvests of grain from the rich Nile River valley served the nutritional needs of Rome. Egypt was to the Empire what Nebraska and Kansas are to the United States and Beauce to France. Excavations have been in progress at Andriake, the harbor of Myra, since 2009. A huge granary was discovered having 7 rooms, measuring 183 feet long and 105 feet wide.

- Acts 27:7 - As the helmsman endeavored to journey westward, he likewise experienced great difficulty fighting against a strong headwind. Upon reaching the port of Cnidus, he decides to travel south to gain protection from northwest winds by sailing under the island of Crete beginning at Cape Salome.

- Acts 27:8-12 - Why did he stop in

Fair Havens? Did he stop here to take on provisions from the agriculturally rich Messara Valley to the north? Did he need to make repairs to the already much buffeted ship? Why did he tarry in this port? If it is such a “Fair” port, why is it not a “Fair” port for winter? To answer that question, one only needs to gaze eastward to fully understand that it is completely vulnerable from that direction. Now, large ocean going vessels wait their turn to load fuel at the

Bunkering Station just offshore.

It is more probable that Fair Havens was nothing more than the last stop before rounding the Southern Cape and once again, being at the mercy of northwest winds. Additionally and perhaps of greater concern, if Northeast winds come racing down the Messara Valley, they will be helpless but to crash into the shores of northern Africa (Syrtis, verse 17). Once they round the cape, it’s a race across a

Twelve Mile Gap to safety.

A reasonable conversation between the helmsman and the owner might have been, “If we can leap that twelve mile gap, we can winter at Phoenix under the shelter of the

White Mountain Range (v .12).” Paul was thinking relatively, “Why take the chance? We could lose everything on that kind of a gamble (v.10)!” The Centurion will make the decision for two reasons.

- First, although this vessel was privately owned, it would surely have been a licenced agent of the Empire to transport grain from Egypt to Italy. There were two famines during the reign of Claudius Caesar, 42 AD and 51 AD. One is directly mentioned by Luke in Acts 11:28. Claudius overhauled the entire operation to make sure it did not happen again. In immediate response to the famine of AD 42, Claudius built a new port at Ostia, and later a much larger harbor at Portus, a few miles to the north, with a lighthouse. Claudius further gave special privileges for shipbuilders to build stronger vessels, and insured owners against storm losses (Suetonius. Claudius 5.18.2 "even in the winter season").

- Second, no one seems to have mentioned another most outstanding fact and surely of the utmost importance; there were state prisoners on board and each soldier (27:42) was under threat of severe punishment if his prisoner escaped. Julius the centurion and his fellow soldiers have the swords! Who is going to argue?

- Acts 27:13 - And then it happened, suddenly. With no forewarning. A southerly breeze comes upon them. Who would have thought such good fortune was to alleviate their perplexity. Yes. Yes! Now is the time to cast off. They should most certainly be able to jump that twelve mile gap. For with a south wind at their backs, the sails are blessed with an extra, generous push in the needed direction. It was only 12 miles but at a speed of 3 to 5 knots that would result in several hours. Warm southern air is not as dense as colder northern air. Hang glider pilots (as this author) have greater control and quicker response while ridge soaring in colder air. But warm air has far less molecules to accomplish the same maneuvers. Travel would have been sluggish. Luke describes the south wind appropriately and translators offer these words: “softly” (ASV, KJV, WEB, YLT) and “gentle” (CEV, ESV, ISV, NIV).

- Acts 27:14,15,16 - Good fortune seemed to prevail for the moment, yet, while hoping for the best, it would still have been difficult to avoid feelings of tension, apprehension, restlessness, uneasiness, or anxiety. It’s only twelve miles. But they were moving so slowly. Then, sudden fortune struck again. But this time is was misfortune. Their worst apprehensions became reality as an extremely violent frontal system raced down from the northeast/southwest Messara Valley, forcing the ship away from the island with absolutely no hope of regaining control. Tempestuous (wind) renders the Greek word

TYPHON, a monster god and the fiercest of all Greek or Roman gods. Typhon was a giant. Eyes of red. Coiled vipers as legs that hissed as he walked. He was the god of violent storms. This author has first-hand experience traveling on the Mediterranean and learning about weather from residents on Greek ships and Greek islands.

Some New Testament translators refer to this storm with the words Hurricane or Hurricane Force. Reference to his name does not indicate a hurricane as the similarity to the word typhoon might suggest. Quite the opposite, our English word Typhoon originates from this god-monster. It points rather to the violent nature of the wind. The Greek god TYPHON represents violence. True hurricanes begin as tropical depressions and take several days to mature. They do not spring up in a matter of a few hours. On the most rare occasions, small cyclonic systems have appeared in the Mediterranean but none have ever achieved even Category 1 on the

Saffir–Simpson Wind Scale or Grade 12 on the

Beaufort Wind Chart.

Understandably, the Mediterranean Sea lacks the enormous amount of heat found at the equator where tropical depressions and inversion layers give birth to hurricanes. Similar to an enormous vacuum cleaner, a true hurricane will suck in air from hundreds of miles with widespread destruction. They may die at the 37th latitude but they begin in the tropics. Mid-latitude converging systems with a little spin do not automatically mean a hurricane.

This can only be frontal activity or the convergence of mid-latitude systems that raced through a funneled valley that points to the southwest from the northeast; thus, it has been correctly termed a “Northeaster.” This violent system came from the northeast and pushed their ship at least 550 miles and perhaps closer to 600 miles to the west. A cyclonic (spinning) storm would have sent them in circles, and most probably crashing into a nearby island - not hundreds and hundreds of miles in a singular direction.

Ancient Greeks spoke of

Twelve Winds, none of which correspond to verse 14. Scholars remain hard-pressed to fully comprehend what Luke originally meant. Friedrich Blass may be correct that it was a hybrid word composed from both Greek and Latin.

| ENGLISH |

GREEK / LATIN |

MANUSCRIPT EVIDENCE |

| Eurakulon |

Ευρακυλων |

U.B.S. Greek NT, Nestle-Aland Greek NT, Metzger: NT Grammar p. 497, Alexandrinus |

| Eurokludon |

Ευροκλυδων |

Beza, Elzevir, Scrivener, Stephanus, Textus Receptus |

| Euroaquilo |

Euroaquilo |

Latin Vulgate, Douay–Rheims |

| Euronotoi |

Ευρονοτοι |

Aristotle: Meteorologica, 363 b22) |

The late renowned Greek scholar A. T. Robertson affirms that this word appears no where else in ancient Greek literature (Word Pictures). Textual Commentator Bruce Metzger states: “The word, which does not occur elsewhere, obviously gave trouble to copyists, who introduced a wide variety of emendations.” Blass terms it: “A hybrid word, compounded of the Greek euro (east wind) and the Latin aquilo (northeast).” And no textual expert has confirmed it to be a verifiable local Cretan term. Aristotle’s description of the wind formation Ευρονοτοι is a southeast wind. Only Luke can possibly know the original spelling and the original meaning.

Summary

It is reasonable to conclude that the persons in control of this vessel decided to sail to the lee or south of the island of Crete to avoid northwest winds that dominate and endanger winter travel on the Mediterranean Sea. Having successfully gained that route, the captain docks at Fair Havens which is the very last port before rounding the Southern Cape. In this last port they contemplated jumping the twelve mile gap bordering the southern opening of the Messara Valley. The idea is to gain winter rest in Phoenix, a harbor more suitably protected by the western mountain range. A gentle southerly breeze encouraged them to make the effort. But somewhere in the middle of that gap, a northeast squall blew down on them from the Messara without warning. The ship was immediately driven beyond their control, narrowly missing a small island. Contrary to a few biblical translations, it was not a hurricane. This northeast frontal system drove them nearly six hundred miles to the island of Malta.

Resources consulted for this article

- Ancient Sailing Season, The - James Beresford

- Ancient Wreck, Clues to Seafaring Lives - William J. Broad

- Classical Dictionary of Biography, Mythology and Geography, A - Smith, Sir William

- Greek Enchiridion (“in the hand” Ἐγχειρίδιον)

- Greek Grammar of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature - Friedrich Blass & Albert Debrunner

- Greek New Testament - United Bible Society v4

- Lateen Sailing Vessel

- Lost Shipwreck of Paul - Robert Cornuke

- Maritime Archaeology and Ancient Trade in the Mediterranean - Damian Robinson & Andrew Wilson

- Meteorologica (Meterology) - Aristotle

- Navigation in the Ancient Eastern Mediterranean, A Thesis - Danny Lee Davis, Office of Graduate Studies, Texas A&M University, 2001.

- Novum Testamentum Graece - Nestle-Aland v28

- Ostia - A Mediterranean Port

- Robertson, Archibald Thomas:

- Sailing Acts: Following An Ancient Voyage - Linford Stutzman

- Secrets of Ancient Navigators - Peter Tyson - NOVA

- Speed Under Sail of Ancient Ships - Lionel Casson

- Testing the Waters: The Role of Sounding Weights in Ancient Mediterranean Navigation - John Peter Oleson

- Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, A - Bruce Metzger

- Wind Scales:

“Sirs, ye should have hearkened unto me, and not have loosed from Crete,

and to have gained this harm and loss.”

Acts 27:21