CHURCH OF THE BRETHREN NETWORK

Continuing the work of Jesus : Peacefully ~ Simply ~ Together

UNOFFICIAL WEBSITE OF THE CHURCH OF THE BRETHREN

|

CHURCH OF THE BRETHREN NETWORK Continuing the work of Jesus : Peacefully ~ Simply ~ Together UNOFFICIAL WEBSITE OF THE CHURCH OF THE BRETHREN |

|

Written by Ronald J. Gordon Published: August, 1998 ~ Last Updated: March, 2013 ©

This document may be reproduced for non-profit or educational purposes only, with the

provisions that this document remain intact and full acknowledgement be given to the author.

|

|

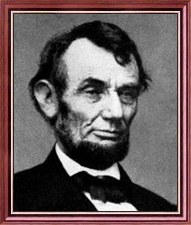

President Abraham Lincoln was committed to preserving the Union when southern States seceded over the issue of slavery. In his letter of response to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley who demanded freedom for all slaves and implied that the Administration lacked resolve, Lincoln states in very plain language his feelings regarding both the issue of slavery and the war. Slavery was not just a political agenda for the South, it was their economic base of agricultural production, their industry, their commerce, their heritage, their way of life. Non-salaried labor was the basis of their plantation system, which powered their industry, which moved their commerce, and offered their standard of living. Compounding the issue was the fact that some in the North either supported slavery openly, or worked to preserve and enjoy the prosperity that also benefited northern States. The former President James Buchanan (1857-1861) endeavored to govern a fast-growing nation that was slowly beginning to fragment over the question of slavery, especially its growing acceptance in the western territories. Political division over this evil was long evident in the eastern States, but the expansion of slavery into the west incited both sides to work more forcefully, because full acceptance in these new territories would give more clout towards determining the final outcome of popular opinion in the east, and subsequently the whole nation. These western States became a hotbed of Slave and Abolitionist activity, in an early concerted effort to sway opinions. Buchanan inherited this problem when his predecessor, Franklin Pierce (1853-1857) and the U.S. Congress repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 with the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 (for the purpose of building a railroad from Chicago to California). The former Act which had banned slavery in the new Territories was replaced with the latter Act which permitted each to decide the issue for themselves. A modest flood of Northerners and Southerners entered Kansas with every intent of swaying opinions and votes in their respective directions, using lobbying, extortion, and murder. When violent hostilities erupted, the spree of killings was suppressed only with the deployment of federal troops. Some historians contend that the Civil War really began in Kansas. Slavers and Abolitionists were tenacious on building their best case for victory, and hopes ran high for political control in the 1860 elections. Abraham Lincoln won the Presidential election mostly because of a splintering of the opposition into a four-way race. This not only left his party holding a narrow margin of political control, but instituted a new departure from the Jacksonian / Democratic control of the previous 32 years. Lincoln was previously known as a strong advocate of freedom, and proponents of slavery in many southern States became enraged. With such an opponent in the White House, their hopes of political control and preserving slavery evaporated before their faces. In just over a month from the November elections, South Carolina seceded from the Union (December 20, 1860) and was followed within two months by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Texas, and Louisiana. The Confederate States of America (CSA) was formed on February 9, 1861.

Buchanan was perceived as a lame-duck for much of his last year in office, because he did not exhibit the leadership or vision that could have avoided bloodshed, Congressional stalemates, and alienation of his own party which resulted in split Democratic tickets in the 1860 elections. It has been suggested that a more aggressive policy toward the West combined with greater statesmanship in the East could possibly have avoided the Civil War, or dramatically reduced the seriousness of any emanate conflict. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the High Court’s landmark opinion in the famous Dred Scott case on the second day of Buchanan’s term in office. The political timing could not have been more unfortunate for the President. Scott had been a slave to Dr. John Emerson and traveled with him through non-slave States. When Emerson died, Scott sued for freedom because he had lived in free territories. The Court ruled that non-citizens (slaves) did not have the privilege of being able to sue in a federal court. Following the election of Abraham Lincoln in November, 1860, Buchanan unofficially introduced a policy of inactivity until he could leave the White House in March of 1861. Historians cite that his lack of interest in State matters during these four months, actually permitted the seceded Southern States to organize themselves more completely. Lincoln inherited a fractured nation with no clear Administrative vision.

“Whenever I hear anyone arguing for slavery, I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally.” - Abraham Lincoln |

Casual students of history are not often aware that Lincoln was frustrated with the problem of creating a Northern “will” to fight, a justifiable reason to take military action against the Southern States. This was not originally a North versus South issue or a national cause of slave versus free. It was a more complex affair that also involved Constitutionality and the Rights of States, wherein some Northerners believed that the southern States had a right to secede, even an appreciable number of Union Soldiers did not see a clear mission for preserving the Union, at least not so intensely as did Lincoln. These northern soldiers saw their southern counterparts fighting for their lands, their families, and their heritage. Many northerners saw the entire matter as a State’s Rights issue with slavery being only the catalyst. Immediately following the attack on Fort Sumter, the actual beginning of hostilities, President Lincoln signed a bill on April 16, 1862, ending slavery in the District of Columbia, nine months before issuing his Emancipation Proclamation to address slavery in the southern States. It brought to conclusion, decades of political unrest by ending what Abolitionists called “the national shame” in the nation’s capital.

Although far short of ending slavery on a national scale, the District of Columbia Emancipation Act served to announce the eventual death of slavery. It provided for immediate emancipation and compensation of up to $300, plus additional payments of up to $100 for former slaves willing to move to colonies outside the United States. The Federal government paid nearly $1 million for the freedom of around 3,000 former slaves. Black citizens of Washington, DC happily began celebrating Emancipation Day on April 16 with parades and social festivities.

Incrementally, a national will to “fight” slowly began to grow in the soil of northern minds, but it was not enough to satisfy Lincoln who wanted to issue a broader Proclamation. This first Act was a good “testing of the waters” to see how receptive would be the concept of Emancipation, in a nation that had greatly benefited from slavery, North and South. Unfortunately, politics and good timing have delayed the best of intentions. Lincoln was waiting for a sterling Union military victory from which to launch his broader Proclamation. Earnestly, he coached and reprimanded Generals toward giving him his decisive victory. Unfortunately, the war dragged on through the entire year of 1861 with no impressive winnings for the Union. In fact, the battle of 1st Bull Run or Manassas was not only a Confederate victory but a Union embarrassment. It wasn’t so much their awkward performance on the battlefield as much as being routed in shame, all the way back to Washington - that’s what made all the newspapers. How could Lincoln boldly issue his Proclamation in view of such circumstances? How does one declare slaves to be free when the slave holders have just kicked your army off the battlefield? How does a President issue forceful demands when his army has just lumbered into town through drizzling rain from a defeat? The Confederacy was jubilant, almost effervescent. The Battle of Manassas (Confederate terminology) is where General Thomas Jonathan Jackson received his nickname of “Stonewall” Jackson. Next to Robert E. Lee, West Point graduate Stonewall Jackson became the most revered of all Confederate generals. A battered and crippled Union army was certainly not experiencing its finest hour, and Bull Run was anything but a launching pad for instituting anything political. Noted writer Walt Whitman, observed the Union army entering the city with these words:

"The defeated troops commenced pouring into Washington, over the long bridge, at daylight on Monday, 22nd - a day drizzling all through with rain. The Saturday and Sunday of the battle (the 20th and 21st) had been parched and hot to an extreme ... But the hour, the day, the night passed; and whatever returns, an hour, a day, a night like that can never again return. The President, recovering himself, begins that very night - sternly, rapidly sets about the task of reorganizing his forces, and placing himself in position for future and surer work ... He endured that hour, that day, bitterer than gall, indeed a crucifixion day, but it did not conquer him - he unflinchingly stemmed it and resolved to lift himself and the Union out of it."

In fairness to the defeated Union commander Irvin McDowell, he simply lacked the necessary training and experience to prosecute the battle of Bull Run (Union terminology). He was suddenly promoted from a junior officer with no theoretical preparation in the craft of warfare, to the command of an entire army, and expected to exercise superior wisdom and execute flawless decisions, plus inspire the troops with a little charisma. McDowell did the best that could be expected under the circumstances. The rest of 1861 and into the summer of 1862 did not provide Lincoln with that sterling victory that he craved. Instead, the battles were either indecisive, stalemates, or marginal victories. Even a marginal victory would be a tenuous platform from which to announce a sweeping Proclamation. A better launching pad would have been not just one definitive victory, but a series of wins to produce enough momentum to launch such an initiative with supreme confidence.

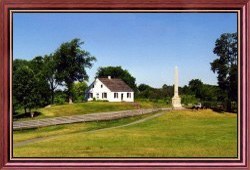

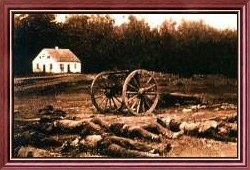

George B. McClellan assumed command of the Army of the Potomac, as the replacement for McDowell following the battle of Bull Run. However, his leadership during the Peninsular campaign was inadequate and immediately after the battle of Seven Days, General John Pope replaced him as the new Union supreme commander. Both armies converged again at 2nd Bull Run or Manassas (August 28-30, 1862), and the Confederates gave the Union regulars a sound whipping. Pope was dismissed and McClellan reinstated. The Army of Northern Virginia was now riding on an air of enthusiasm, almost superiority. Only tactical failures on the part of Generals Jackson and Longstreet deprived Lee of the total destruction of Pope’s army. General Robert E. Lee decided on a bold new vision to bring the Union into submission - not by attacking Washington itself - but by taking the war into the northern States. Lee was hopeful that human suffering and property loss on Union territory would arouse discontent and pressure Lincoln to acquiesce to Southern demands. This decision would eventually bring both armies together at the Battle of Antietam, in front of a peaceful Little Dunker Church."

President Lincoln continued to wait patiently for that sterling Union victory that would cripple, if not crush the Confederacy, firmly preserve the Union, and give him the platform that he needed to issue his Emancipation Proclamation. But the war hopelessly dragged on. In the meantime, debate over slavery widened political gaps and encouraged prominent citizens to take actions on their own. Many politicians believed that the U.S. Constitution protected slavery, whereas others, such as Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner contended that the President had the legal authority to abolish it. General Benjamin F. Butler, a fierce opponent of slavery, was placed in command of Fort Monroe in May, 1861, a garrison located in Virginia. Not too long afterwards, runaway slaves began appearing at his fort in the hopes of being given protection from their masters. Slave owners appealed to Butler for the return of their “property” but he refused, on the grounds that the slaves were “contraband of war.” Butler skillfully crafted his personal opinions in stately legal language, in an attempt to gain their freedom. He became an instant personality and bold figurehead to Abolitionists. Lincoln viewed Butler’s action to be unconstitutional but was advised by his Cabinet that it would not be politically expedient to reprimand the General. Only a few months later, Major General John C. Fremont, commander of the Union Army in St. Louis, announced that all slaves owned by Confederates in Missouri were free. When asked by President Lincoln to slightly modify the language of his directive, Fremont refused and was later dismissed for insubordination. So emotionally charged was the issue of slavery, and so volatile the opportunities for permanent damage to national interests, that Lincoln had to constantly tip-toe around these numerous encumbrances in order to end slavery as he thought best, without angering the greatest number of people, especially his advisors and loyal friends.

The Battle of Antietam was a “sterling stalemate” yet it did give President Lincoln the best opportunity, thus far, to launch his quest of ending slavery. Although the lines of battle had not significantly changed during this conflict, it firmly eclipsed Lee’s bright vision of invading the northern States. Five days after the battle, Lincoln announced that he would issue an Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, irrevocably announcing to the South and the world, that this War was more than a State’s Rights issue - it was a moral cause to end a barbaric economy in human flesh.

If not a sterling victory, why then did Antietam stand out from the litany of battles that dotted the countryside around Washington and Richmond. There are probably several factors, none-the-least being the sheer number of casualties and the first opportunity for Americans to view dead bodies on a battlefield. It took so long to bury the huge number of soldiers and burn the piles of animals, that Matthew Brady assistant Alexander Gardner was able to move his equipment around the battlefield for several days. He took ninety-five wet plate negatives of the grotesque and contorted figures of men and boys - forever frozen in time. Gardner and Brady shocked America with these photographs. The nondescript sign on the door of Brady’s New York gallery read: “The Dead of Antietam.” The New York Times said that Brady had brought “home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war.” Lee’s vision of progressing into the northern States being thwarted, provided Lincoln with a stellar if not sterling victory.

A terrible pause gave many the opportunity to realistically think about what this divided nation was doing to itself. After two years of war, thousands upon thousands, and more thousands were dead. Was preserving the Union worth this much? Was preserving slavery worth this much? Battlefield after battlefield, gorged with dead bodies taking days to bury. Is this the American message of freedom? Is this what Thomas Jefferson had in mind when he penned the opening statement of the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” What does unalienable mean? Merriam-Webster [ Etymology: probably from French inali譡ble, Date: circa 1645 ]: incapable of being alienated, surrendered, or transferred. The framers of this document wished to convey that people are “endowed by their Creator” with Rights that only a “Creator can issue?” Although slave holders, legislatures, and courts preferred to interpret these words much differently, slavery was none-the-less viewed by many as a repudiation of these original thoughts. Slavery was a barbaric interruption in the life of the nuclear family, from which is provided a nations stability. It was a philosophic enemy to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

How and where did this destructive economy in humans beings originate? What were the precipitous conditions for its planting and growth in the southern States? This social plague is at least as old as the Bible. For in the very first book, the writer of Genesis tells the story of Joseph the Patriarch who was sold by his own brothers to Ishmeelites for twenty pieces of silver, who then resold him upon arriving in Egypt. Generations later, the Egyptian royalty began to fear that this quickly multiplying population of foreigners would eventually destabilize their own culture, so they forced them into slavery. Hebrew slaves were mercilessly pressured by the Pharoahs to labor in the construction of huge cities. Only with the intervention of Moses the Deliverer, along with the plagues from God, were they able to escape from captivity. Selling people for profit was surely not the original idea of these few brothers, but more probable their continuation of a social evil that was already prevalent. Throughout history, other subjugated people would also yearn for their own Moses.

Aristotle

History, in part, seems to be a continuous narrative of one group subjugating the freedoms of another. Slavery has overshadowed every century of recorded history. It existed in ancient Babylonia, for laws governing slaves can be found in the Code of Hammurabi. Aristotle taught that human beings are not equal, that some are born to be subjugated while others seemed destined to rule: “For that which can foresee by the exercise of mind is by nature intended to be lord and master, and that which can with its body give effect to such foresight is a subject, and by nature a slave” (Aristotle/POLITICS). Slavery in ancient times was not restricted to skin color but encompassed people from all cultures, and due more often to the fateful outcome of circumstances. Dark-skinned Romans owned white slaves and white-skinned Romans owned dark-skinned slaves. In contrast, Orlando Patterson, Professor of Sociology, called slavery a social death. He concurs that all societies have some form of hierarchy with different degrees of honor and respect: someone is always at the top and someone is always at the bottom even though equality for all is maintained by law. But Patterson interjects that slaves have no honor, they are stripped of respect, they are chattel for exploitation by others. Patterson concludes that slavery is therefore not the natural life of a hierarchical society but a sign of its emanate death.

Diogenes

...pronounced (dye-ODDG-e-neez), was a famous Greek thinker and founder of the Cynic school of philosophy. It is said that he wandered through the streets of Athens, even at night with a lantern, in the search for an honest man. Plutarch relates the story of how Alexander the Great, upon receiving individual congratulations by the nobles of Corinth for becoming commander of the entire Greek army, noticed that Diogenes was absent. Curious to know for what reason one might exclude themselves from such an occasion, Alexander went searching and found him relaxing in his famous tub under the bright Mediterranean sun. “I am Alexander the Great,” said the general. “I am Diogenes the Cynic,” replied the philosopher. “What service might I render you today,” said Alexander. “Stand from between me and the sun,” said the Cynic. Alexander was so impressed, yet amused, with the haughty independence of the philosopher that he later told friends: “If I were not Alexander, I should wish to be Diogenes.” With a possible jest at humor, coupled with a degree of sincerity, he is often remembered for one of his most memorable quotes: “The art of being a slave is to rule one’s master.” Ironically, he was forced to adhere to his own advice when captured by pirates on a voyage to Aegina and sold in the slave markets of Crete. While standing on the slave block the auctioneer asked Diogenes if he had any particular skills, to which he replied: “I can govern men; therefore sell me to one who wants a master.” Xeniades, a very wealthy Corinthian was struck by such a demonstration of paradoxical comedy that he purchased the old philosopher. Upon their arrival at Corinth, the hometown of Xeniades, Diogenes was given his freedom with the stipulation that he accept full responsibility for the education of the family children. A task which Diogenes faithfully administered until his death.

National Enslavement

The Roman Empire practiced mass enslavement of many subjects as they conquered new territories. Inhabitants immediately found themselves to be property of the Roman state, to which they served in a wide variety of tasks. Depending on the whim of their new masters, they were usually separated into one of two classes, public and private. Some private slaves worked in the fields with no more privileges than cattle, while others became house slaves with a modest degree of respect. Public slaves accepted roles in government, becoming magistrates, executioners, jailers, and even priests.

Norsemen routinely raided the European continent from their longboats. Between the Nineth and Eleventh Centuries, there were very few parts of Europe that escaped being plundered by the Vikings. In 845, Charles the Bald, King of France, paid tribute to Ragnar to relieve his attacks on Paris. Other monarchs did likewise to escape the certain pillaging of their villages, looting of monasteries, wanton killing of the populace, confiscation of their crops, rape of their women, and transportation of their people into slavery. Danes imposed a regular tax on the people of Ireland and slit open the noses of those who did not pay. Hence, the origin of the phrase: “Paying through the nose.” A common prayer of the time was: “A furare normannorum libera nos, Domine” (From the rage of the Norsemen keep us, Oh Lord).

African Slave Kingdoms

The real origin of slavery in America begins in west African Slave Kingdoms, such as Dahomey and Ashanti. Long before Europeans arrived to purchase their human produce, these kingdoms trafficked in slaves and accumulated enormous power and wealth. English, French, Spanish, and Dutch slavers were initially only junior partners with these African potentates; and upon their arrival, they discovered well established financial networks and political organizations. Without individual ownership of private property in these lands, a persons wealth was measured in the number of slaves that he possessed, in addition to other particulars. Before the advent of military hardware that permitted the overthrow of such kingdoms during the period of global colonization, Europeans desiring minerals and other treasures from the heartland of Africa were at the mercy of these elite coastal rulers and merchants. Gradually, a commercial market and distribution network for slaves evolved between these kingdoms and their European customers. Since the western coast of African is a hazardous repetition of offshore reefs and shifting sandbars, American slave ships waited beyond, at anchor in the safety of deep water. Canoes filled with slaves were piloted around these reefs by fellow Africans. It is naturally disheartening for many African Americans to learn of the complicity of their ancestors in the victimization of their fellow countrymen. However, there were noticeable differences between the more brutal American slavers and their African counterparts. Although slaves in African were acquired most often through warfare or mass kidnappings, they were treated more like indentured servants with certain rights and privileges, such as their children being free at birth, and their ability for eventual release into the care of related family clans. This was rarely the circumstance of slaves sold to Europeans, for they were immediately stripped of any rights and treated as chattel, plus their children became slaves at birth.

Large plantations in the West Indies served as the main producers of sugar and tobacco. Initially, local Indians were constrained into slavery but ill-treatment, brutality, disease, and periodic mass suicides soon led to their demise. European white indentured servants were used for a short period of time but they could not endure tropical conditions and began dying in alarming numbers. In haste to maintain shipping schedules and profits, criminals and political prisoners were forced to work on these West Indies plantations but they suffered from the same environmental scourges as the indentured servants. A new source of cheap, environmentally friendly labor was needed - Africans. Some historians contend that the Africans were also better laborers than the Caribbean Indians because they came from a more advanced society of skilled artisans, whereas the former were generally unskilled food gatherers.

In 1672, the British Parliament created the “The Royal African Company” to maintain profits as trade with the Caribbean colonies increased. A nation that formerly eschewed slavery now sanction its existence in order to protect the interests of wealthy London merchants. Need for human chattel grew rapidly and slaving became big business. In cooperation with the West African Slave Kingdoms, coastal forts with holding pens were built and contractual agreements put in place, including tariffs for outside companies looking to buy slaves. During the 1680s, an average of 5,000 slaves per year were shipped to the Caribbean plantations. Slaves became so valuable that they were eventually called Black Gold.

Slavery In America

The actual beginning of slavery in America is not easily documented, but often related to the exchange of twenty black persons for food by a Dutch merchant ship at Jamestown, Virginia, in August of 1619. They were arguably more like indentured servants than slaves, and most eventually gained their freedom. Indentured Servitude was a common practice whereby financially distressed emigrants wishing to leave their European homeland would pay for the cost of their travel by “indenturing” themselves to work for their sponsor over a specified number of years, at which time they were free. Gradually, the demarcation between indenture and slavery became blurred as servitude of one type or another was necessary to accomplish the increasing amount of work in this new nation. The first public slave auction was held in Jamestown square in 1638. Rising demands for cotton, sugar, and tobacco were creating a greater demand for cheaper labor.

Black Gold gradually became the main source of labor due to several reasons, including the original supply of labor from indentured servants in America having largely disappeared by 1680. Cotton was the prime export of the American southern States, and tobacco was the northern counterpart in Maryland and Virginia. States gradually began legalizing the ownership of slaves, largely to reflect the already institutionalized status of their population classes. The race for cheap slave labor had commenced, and in the ensuing years, a flood of millions were transported to American farms and industry. The very nation that was founded on the principals of “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness,” shamed itself by institutionalizing the eradication of life, liberty, and happiness for millions of its citizens.

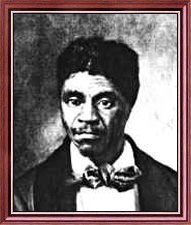

Dred Scott

|

| Dred Scott |

...was a slave who put a face on the issue of slavery. After eleven long years of litigation through state and federal courts, the United States Supreme Court ruled in March of 1857, with a landmark decision, that slaves were non-citizens and therefore could not sue in a federal court. The Justices also ruled that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 was unconstitutional because it deprived people of their property (slaves) without due process of law. The United States paid France $15 million for the Louisiana Territory in April, 1803. Predictably, discussion over the expansion of slavery into this region prompted the U.S. House of Representatives to introduce legislation in 1819 that would give statehood to Missouri while prohibiting further expansion of slavery into the new State. The next year, a compromise was reached that admitted Missouri into the Union as a slave State, with the stipulation that slavery would not be permitted above the latitude of 36º 33’ N. By rescinding the Missouri Compromise, the High Court was effectually ruling that slavery must be legal in “all” States because prohibiting slavery in any State would violate the traveling slave owner’s right to own and retain property - a sort of reverse Emancipation.

This ruling actually had the effect of saying that all Blacks, slave or free, could never become citizens of the United States. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, a firm supporter of slavery was intent on protecting Southern interests from Northern manipulation. Dred Scott had been a slave to Dr. John Emerson, a US military surgeon who traveled considerably. In 1834, Emerson left Missouri with Scott for the military post at Rock Island, in the non-slave State of Illinois. Two years later, while living at Fort Snelling, Emerson purchased another slave named Harriet. Dred Scott and Harriet married and produced two children, Eliza and Lizzie. In 1838, Emerson moved back to Missouri (slave-State), taking Scott’s new family along with him. When Emerson later died, Scott sued for freedom because he had lived in a free State. In the majority opinion,

Chief Justice Taney said “(black men) ...had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic, whenever profit could be made by it.” Referring to the Declaration of Independence which stating that “all men are created equal,” Taney reasoned that “it is too clear for dispute, that the enslaved African race were not intended to be included, and formed no part of the people who framed and adopted this declaration.” In these years immediately preceding the Civil War, the lines of demarcation between the intentions of Slavers and Abolitionists grew steadily more clear. Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis resigned from the High Court in protest of the ruling. Mrs. Emerson, the widow and legal owner, decided afterwards to free Dred Scott.

In 1865, when the bloodshed of over 600,000 men and boys had finally ended and the nation began healing itself through a process of reconstruction, the mere mention of the Dred Scott decision still angered many people, and especially those in the Republican controlled Congress. It was a normal and customary request upon the completion of a term of service as Chief Justice to the Supreme Court, that a commemorative bust of the Chief Justice be placed along side of other Supreme Court Chief Justices. When application was made for a bust of Justice Taney, Senator Charles Sumner, U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, led the opposition that blocked the request with these scathing words:

"I speak what cannot be denied when I declare that the opinion of the Chief Justice in the case of Dred Scott was more thoroughly abominable than anything of the kind in the history of courts. Judicial baseness reached its lowest point on that occasion. You have not forgotten that terrible decision where a most unrighteous judgment was sustained by a falsification of history. Of course, the Constitution of the United States and every principle of Liberty was falsified, but historical truth was falsified also."

US Slave Population

In 1680, the slave population of the South was slightly less than 10%, but that swelled to just over 30% by 1790. Virginia had about 293,000 slaves and nearly 100,000 for Maryland. Following the American Revolution, the slave population in the South exploded to nearly 1.1 million in 1810, and exceeded 3.9 million by 1860. Slavery was becoming an institutionalized economic base of its industry. With the election of freedom advocate Abraham Lincoln in 1860, southern States became enraged and seceded in order to preserve both their heritage and their source of labor.

Cornerstone Speech

There are those who will argue that the Civil War was fought over the secession of the Southern States, the need to preserve the Union, and not over slavery. These are Northern voices who sought to preserve their heritage of freedom, a nation of opportunity. But the Confederate States of America was formed by other voices who wanted to preserve a different heritage. A heritage of subjugation. A heritage that affronts common decency when families are torn apart for the financial advancement of others. A heritage that rejoices when another human being is manacled and treated like an animal. It was a heritage of prosperity enjoyed by those who maintained slavery. Historians must be able to understand and explain both sides of this conflict. Union soldiers may have been fighting to preserve the Union, but the Confederate soldier was fighting for nothing other than to preserve a heritage of slavery. He was fighting for the ideas of Alexander Stephens, the vice-president of the Confederacy who enunciated in his famous Cornerstone Speech: “Our new Government is founded upon exactly the opposite ideas; its foundations are laid, ITS CORNERSTONE RESTS, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and moral condition. This, our new Government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.” These States wanted to preserve a heritage that would subjugate an entire race of people, esteem people of color as intellectually inferior, sell them as common livestock, maintain two separate systems of justice, and perpetuate the horrid injury of separating children from their biological parents. The Northerner may say that the Civil War was fought to preserve the Union, but the Southerner will say that he was fighting for no other cause than to disrupt the Union and preserve the institution of slavery.

Mississippi Secession

“Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery-- the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization.”

Texas Secession

“She was received as a commonwealth holding, maintaining and protecting the institution known as negro slavery-- the servitude of the African to the white race within her limits-- a relation that had existed from the first settlement of her wilderness by the white race, and which her people intended should exist in all future time.”

Constitution of the Confederate States of America; March 11, 1861

Article IV, (3): “The Confederate States may acquire new territory; and Congress shall have power to legislate and provide governments for the inhabitants of all territory belonging to the Confederate States, lying without the limits of the several Sates; and may permit them, at such times, and in such manner as it may by law provide, to form States to be admitted into the Confederacy. In all such territory the institution of negro slavery, as it now exists in the Confederate States, shall be recognized and protected by Congress and by the Territorial government; and the inhabitants of the several Confederate States and Territories shall have the right to take to such Territory any slaves lawfully held by them in any of the States or Territories of the Confederate States.”

True to his word, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, stating: “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious States “...are, and henceforward shall be free.” Many have charged that this Proclamation was lame from the beginning, for it applied only to States that had seceded, and actually exempted some territories that had recently come under Union control. This is all true, however, this action must be understood in light of the national politics and culture of that day. It was a bold move for that period. No other President had actually contemplated such a daring move. After January 1, 1863, the aspect of the war experienced a fundamental change; for now it became a moral cause for freedom, something for which everyone could identify. One unknown statesman explained: “Mr. Lincoln has now put a face on the war.”

With each new victory, Union troops not only gained territory but also liberated slaves and expanded the cause of freedom. Many former slaves then joined the Army of the Potomac to become liberators themselves, which gradually turned the Union forces into an army of liberators. President Lincoln was trying to occupy the moral high ground. Over the next few years, several Black Regiments and Companies appeared in the Union Army, and by the end of the war, almost 195,000 black soldiers and sailors had served under the Union colors. In spite of foreign criticism over the noticeable inadequacies of the Proclamation, Lincoln defended it as a necessary: “act of justice.”

Not all white northern Americans shared Lincoln’s moral perspective, especially in New York State where politicians and newspapers convinced many, and particularly Irish immigrants, to fear black competition for their jobs. Abraham Lincoln issued the Enrollment Act of Conscription on March 3, 1863, in an effort to supply necessary troops to his generals. Predictably, many did not like the idea of conscripting or drafting their young men into the service, and many loyalists were just getting tired of a two-year-old war that had no resolution in sight. Riots erupted in Toledo, Cincinnati, Harrisburg, and Detroit, but the ones in New York City received most of the attention because they were the most violent - the most violent peacetime uprising in United States history. A powerful Democratic opposition ran the city and Horatio Seymour, the popular Democratic governor, openly despised President Lincoln. The names for the first draftees were called on July 11 in New York City, and politically ill-timed for the Republican President because reports from the bloodshed at Gettysburg were just being published in the local newspapers. It was not a good time to call for the enlistment of 300,000 more men to die in a protracted war. Compounding the situation even further, was the inclusion in the law of a “commutation fee” that could excuse wealthier men upon payment - a sure guarantee to widen social class divisions. This newly enacted conscription law with its exclusions, plus the whole concept of Emancipation, mixed with a little propagandized misinformation, suggested to some whites that they would be conscripted into the army to liberate blacks who might then move north, taking their jobs and marrying their daughters. Riots broke out on July 13, 1863, and lasted for three days. Impoverished Irish immigrants living in the slums of New York City, and competing with blacks for the lowest paying jobs, banded in mobs that numbered into the thousands. Although blacks were chiefly their targets, wealth also garnered their attention, for they vandalized whole neighborhoods, looting many stores, lynching at will, burning the Colored Orphan Asylum, ravaging the Colored Seamen’s Home, and burning one black church. Lincoln sent Federal troops to the city to quell the uprising, and at one point, soldiers even fired canisters of grape-shot into some mobs. Peace was ultimately restored.

Themes play an important role in the development of our belief systems and our endeavors to understanding history. Truth is often an elusive quest or a mystical formulation hanging between variant opinions. Themes help us to clarify our understandings. If one were to examine bibliographical lists of books on the Civil War, they would surely number in the tens of thousands. Predictably, writers offer their own conclusions to the events of this time. Perhaps the most common question being: “Was the Civil War fought over slavery, or the secession of Southern States?” It may depend on which State you were born and raised in, the color of your skin, which drinking fountain you stood before, or the personality of your high school history teacher. History is not like mathematics. It does not lend itself to concise theorems or predictable calculations. Unless there is video tape or film, the broad colorful, multidimensional expanse of any event is too immense to be archived by the finiteness of human intellect. Some will contend that the Civil War was fought over the secession of Southern States, but this is, characteristically, a Union way of looking at the matter. It’s only half of the coin. But what was the Confederacy fighting for? Why did the Southern States secede in the first place? Why did the seceded States go to war, first? Why did General Beauregard demand the surrender of Fort Sumter? Why did Southerners pour into Kansas? Why did William Quantrill scatter blood in Lawrence? Why did John Brown and his four sons murder proslavers at Pottawatomie Creek? Why did the term “Bleeding Kansas” arise? Why do a few Southerners still take pride in flying the Confederate flag? Why do African Americans yet discuss, with remote expectation, the merits of Reparations? Only one word will satisfactorily answer each of these questions. Heritage. The Civil War or the War Between the States was fought over Heritage. For the Union this meant preserving its unity of States, and for the Confederacy it meant preserving slavery. Each was trying to preserve their own cultural understanding of Heritage.

Slavery was the Heritage of the Confederacy. It was the broth of the stew, the fuel of the fire, the wind of the storm, and the heat of the sun. Slavery was a distinct cultural thread, inextricably woven throughout its fields and factories, stores and shipyards, gardens and vineyards. Slavery was the conspicuous theme of Alexander Stephen’s famous Cornerstone Speech and the energy that propelled Rebel troops toward Union entrenchments. Slavery was not just an issue. It was the only Issue. The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 was President Abraham Lincoln’s response to that Issue.

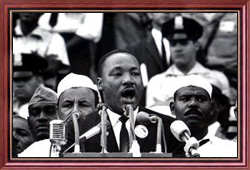

Let Freedom Ring

On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. on August 28, 1963, under the very gaze of the Abraham Lincoln statue, Dr. Martin Luther King stated these historic words to multiplied thousands who surrounded the Memorial and lined the Mall Reflecting Pool:

“Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

Dr. Martin Luther King |

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we have come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

In a sense we have come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked "insufficient funds." But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time, to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time, to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.

and to underestimate the determination of the Negro It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. And there will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny, and they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, "When will you be satisfied?" We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victum of the unspeacable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating for whites only. We can never be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive.

Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal."

I have a dream - that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood.

I have a dream - that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream - that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream - that one day, down in Alabama, with its visious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification. One day right now in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream - that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day, this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with a new meaning, "My country, ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim’s pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring."

And if America is to be a great nation this must become true. And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania.

Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado.

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

But not only that, let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee.

Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!"”

Additional Resources:

Photo Credits:

All modern photographs by Ronald J. Gordon © 1998, 2002. Other photographs, images, or reproductions are displayed with respect to intellectual property and compliance to all known Copyrights.

Bibliography:

A complete listing of all resource materials involved in the production of this resource can be found at the bottom of the home document. Included are hard print literature, numerous maps, graphic images, and links to related web sites. Unlisted are numerous trips to the battlefield, visits to associated congregations, and personal interviews.